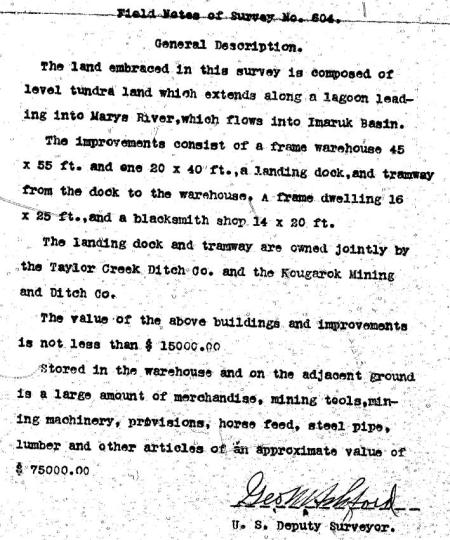

By Gabe Emerson

This list was created to document the many forgotten short-line railroads of Alaska. It covers the small and mid-size lines that only went a few miles or only lasted a few years. It does not deal much with the larger railroads like the AKRR and the CRNWRR that are well-documented elsewhere. This page is a work in progress and will hopefully one day (after much editing and improvement in layout) become a printed book. More explanation is after the index listing, or you can jump straight to the section you’re interested in!

Links to individual listings:

Livengood Railroad / Tolovana Tram

Treadwell Mines Railroad

Cook Inlet Coal Fields Railroad

Iyoukeen / Gypsum Railroad

Pinta Bay / Goulding Harbor Railroad

Lockanok Tram

Killisnoo Tramway

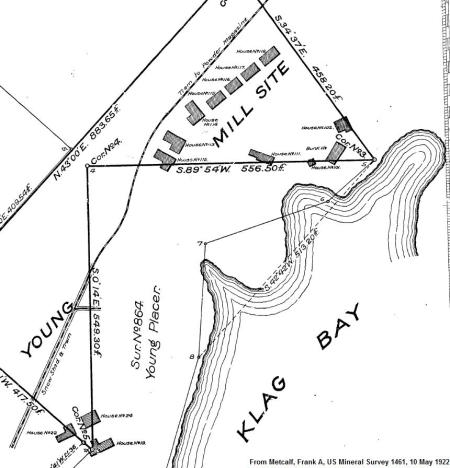

Eagle River / Amalga Harbor Tram

Dry Bay Railroad

Nugget Creek Tram

Loring Hatchery Tram

Pribilof Island Trams

Chickaloon Tram

Sitka Pulp Mill Yard

Ward’s Cove Pulp Mill Yard

Valdez Railroads

Saxman Barge Terminal

Trans-Alaska Railroad / Alaska Short Line Railroad

Rush and Brown Mine Railroad

New Boston Mine

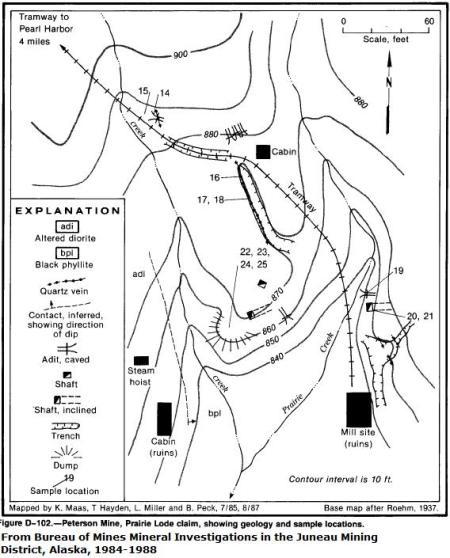

Peterson Mine / Pearl Harbor Tram

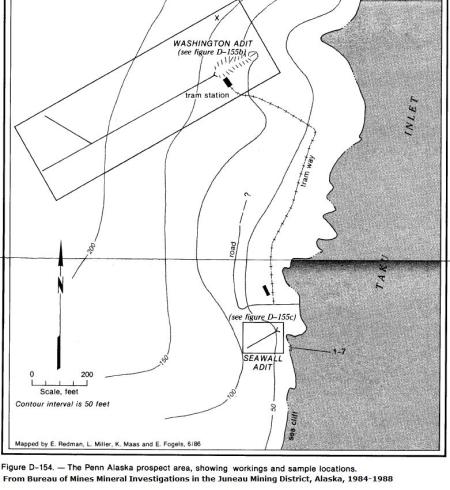

Penn Alaska Tram

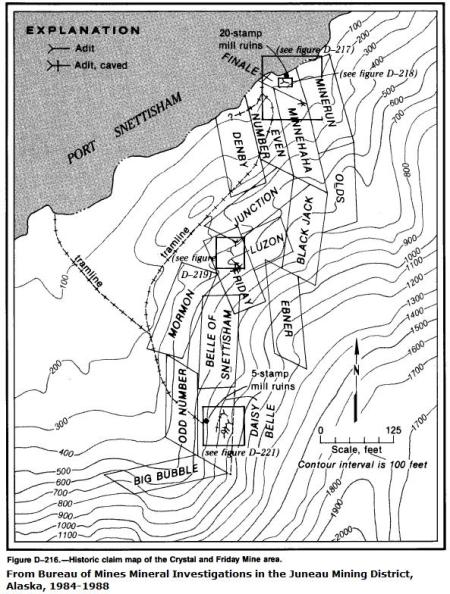

Crystal and Friday Mine Tram

Rodman Bay Railroad

Lucky Chance Mine

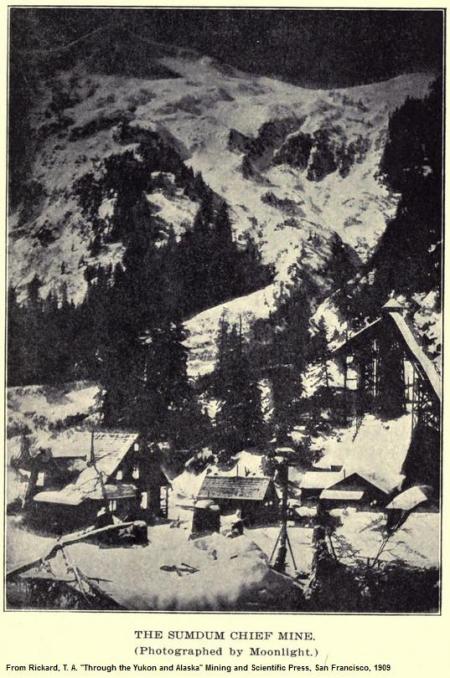

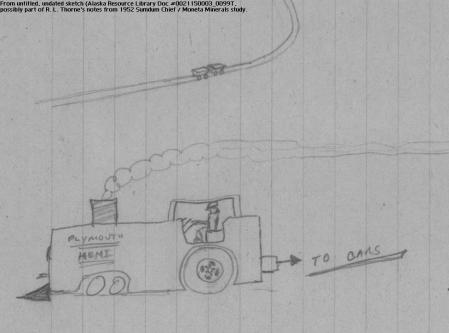

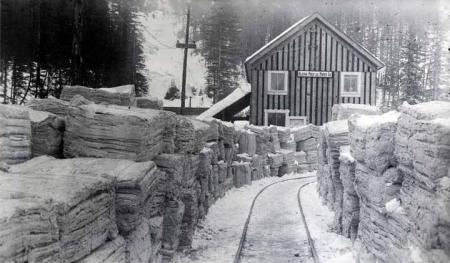

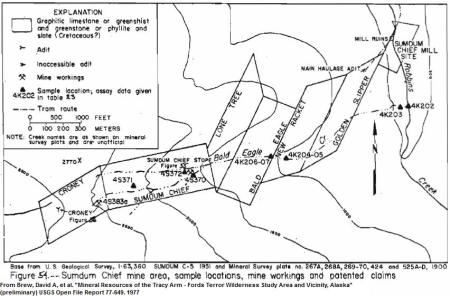

Sumdum Railroad

Funter Bay Railroad

Windham Bay Tramways

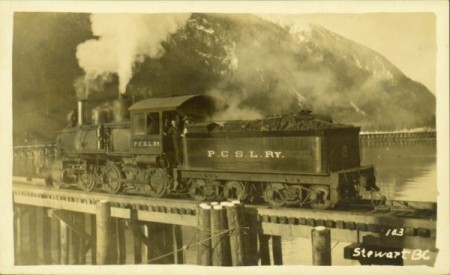

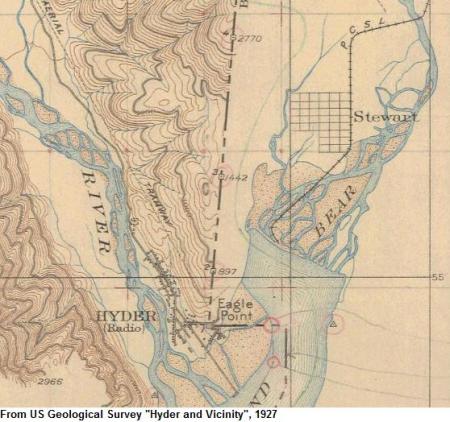

Portland Canal Short Line Railway

Oliver Inlet Portage

Teller Tram

Alaska Pulp & Paper Co Tramway

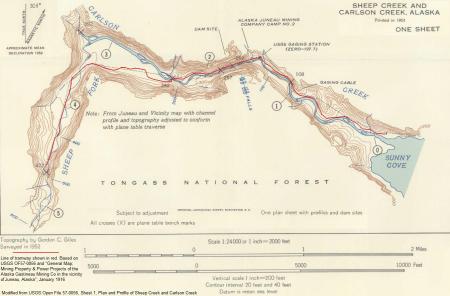

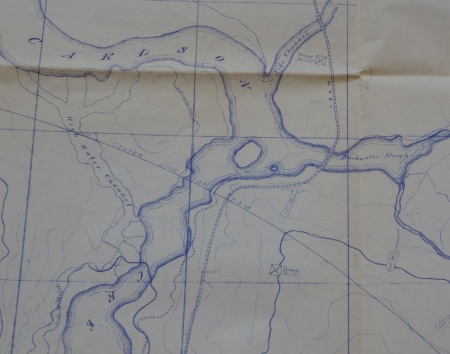

Carlson Creek Tram

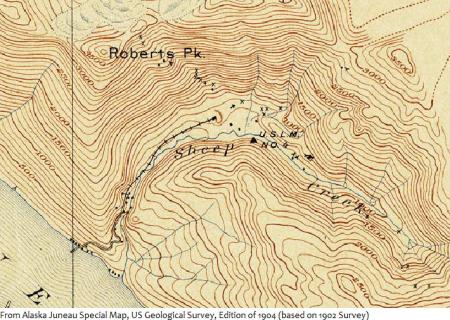

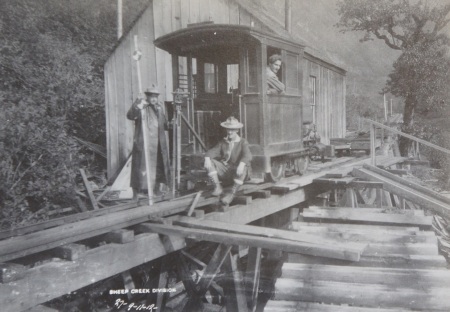

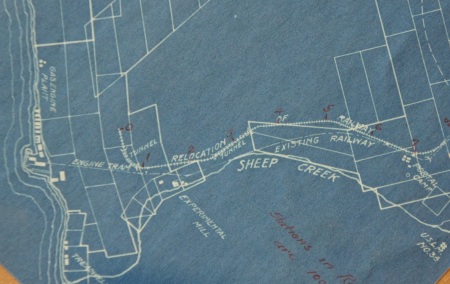

Sheep Creek Railroads

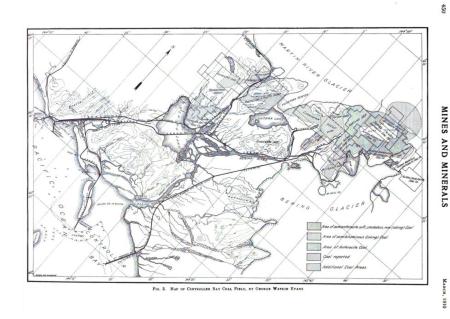

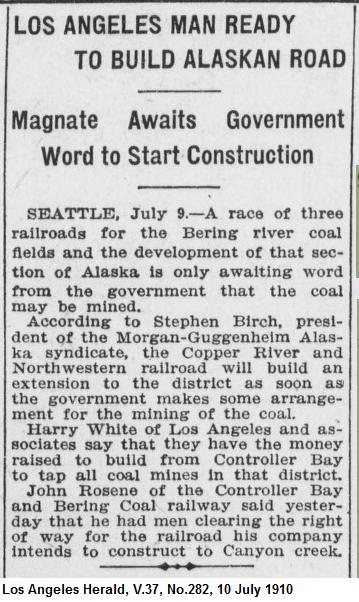

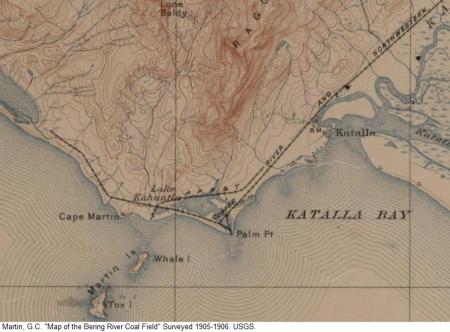

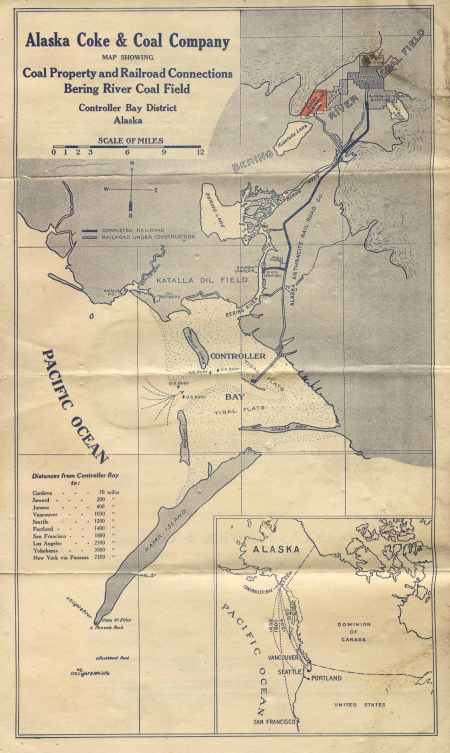

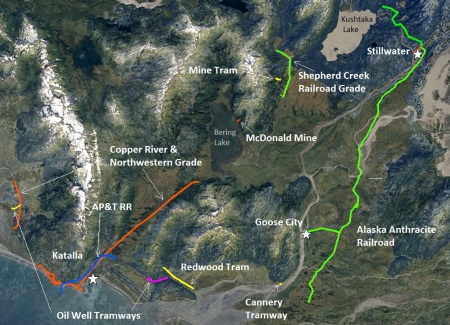

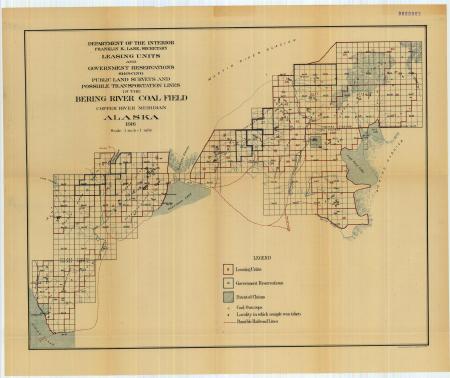

Katalla / Controller Bay Railroads

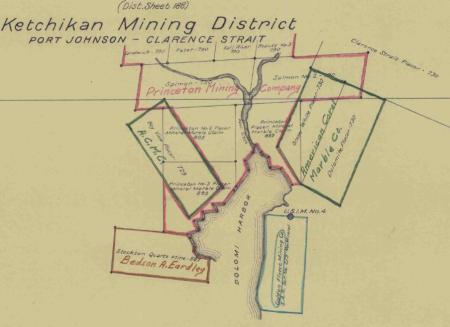

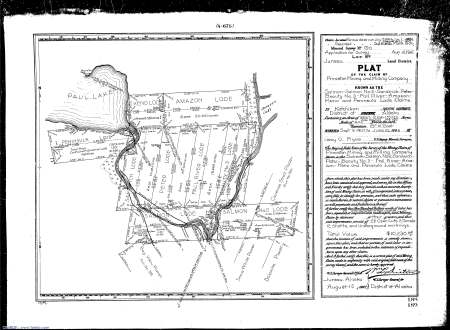

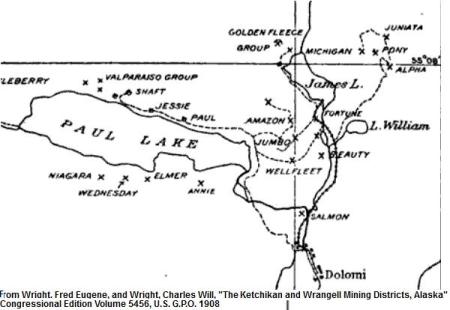

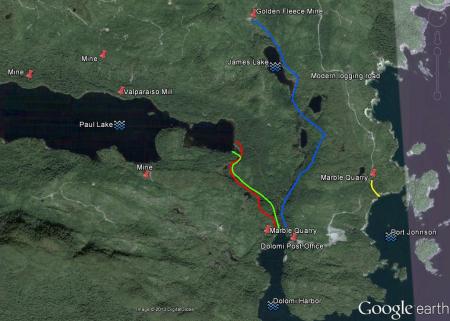

Dolomi Lines

Cymru Tram

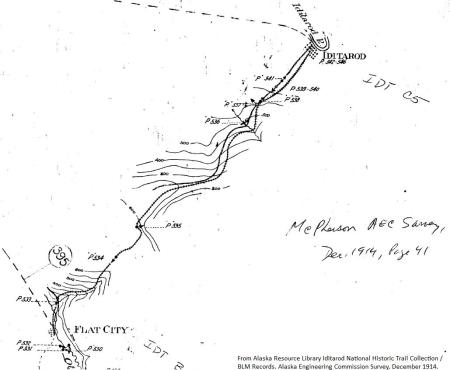

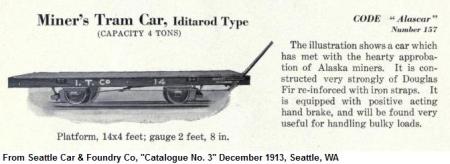

Iditarod & Flat Tramroad

Sulzer Tram

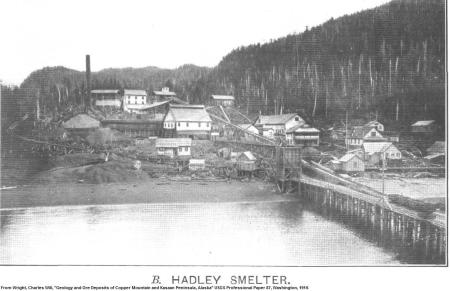

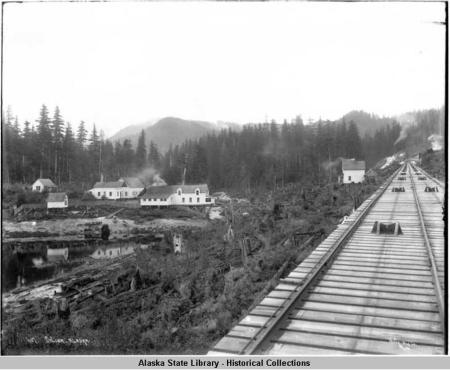

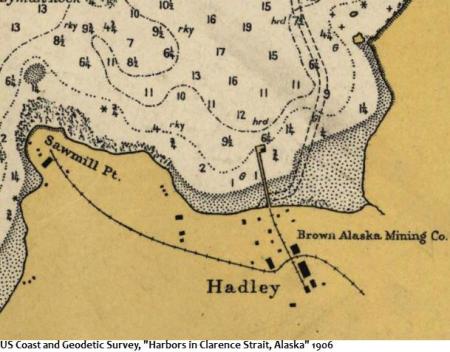

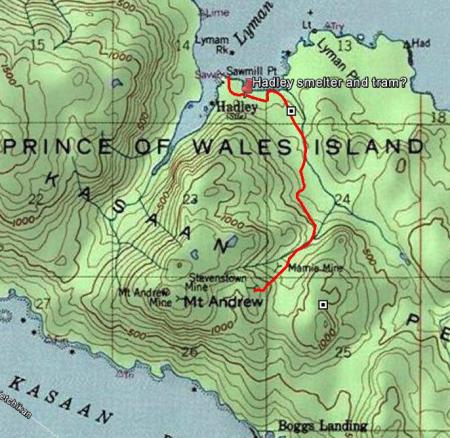

Hadley Tram

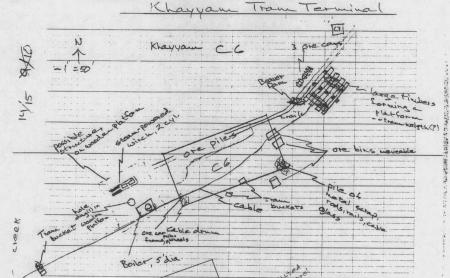

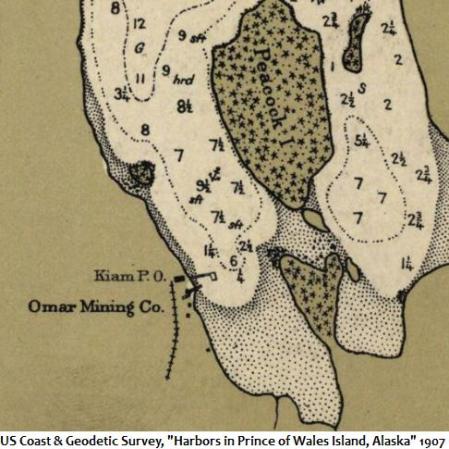

Kiam Tram

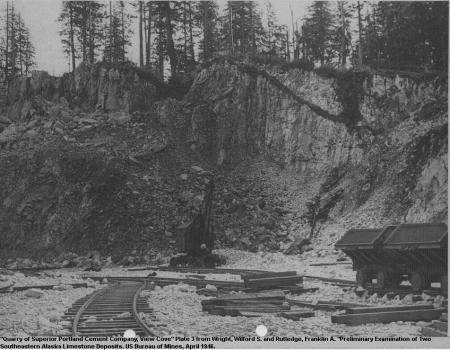

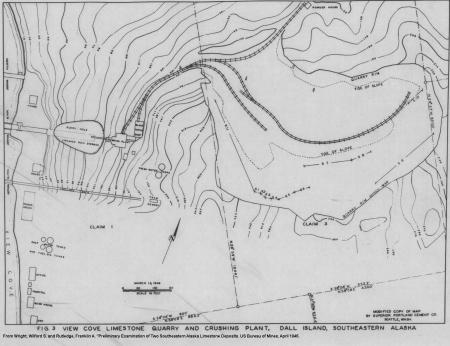

View Cove Tram

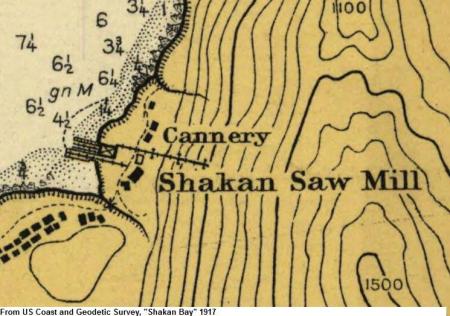

Shakan Trams

Calder Funicular

Ketchikan Funicular

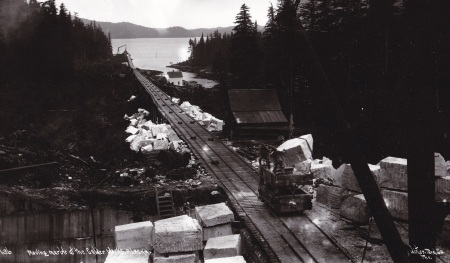

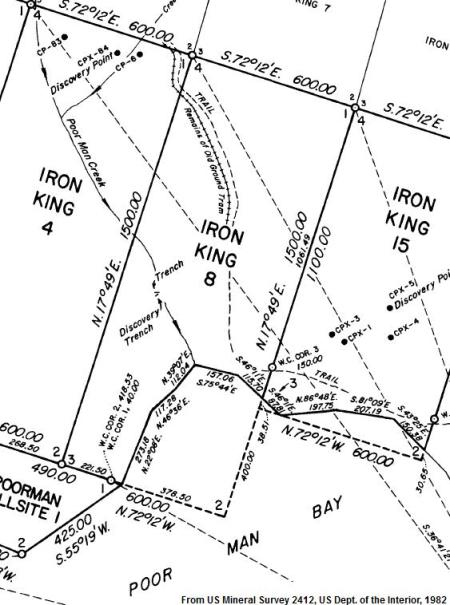

Poor Man Mine Tram

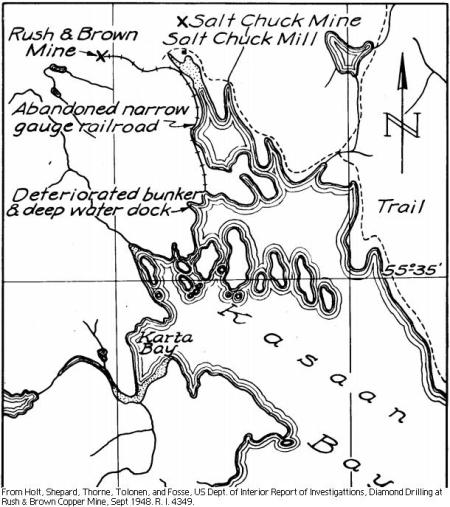

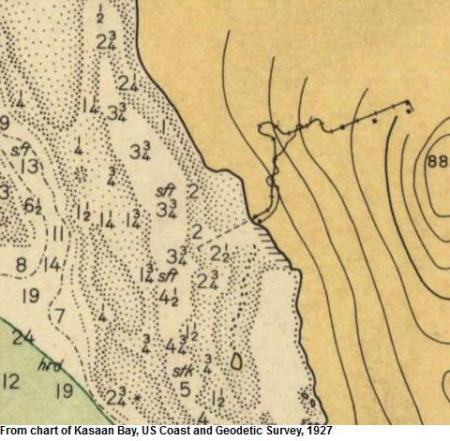

Kasaan Tramway

Latouche Tramway

Chititu Tramway

Elephant Point Tram

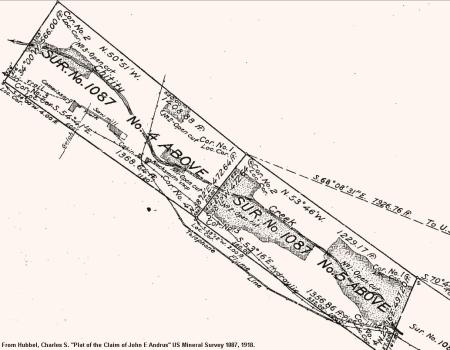

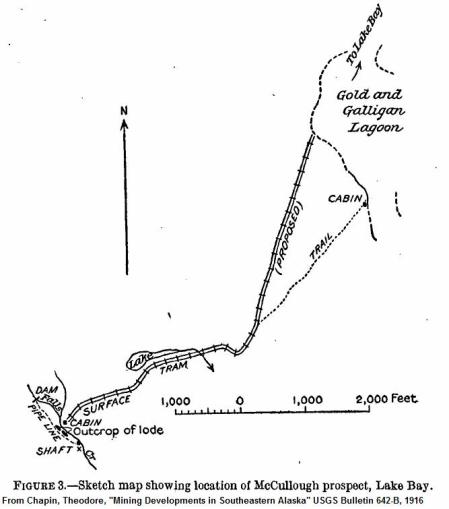

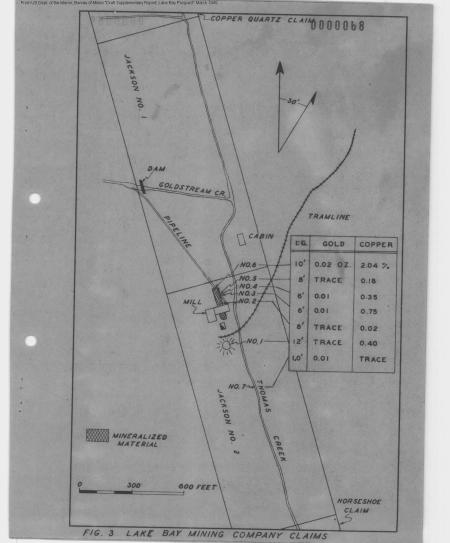

Lake Bay Mine Tram

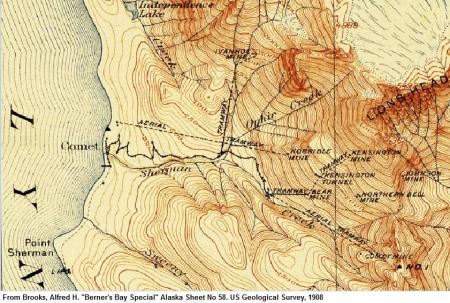

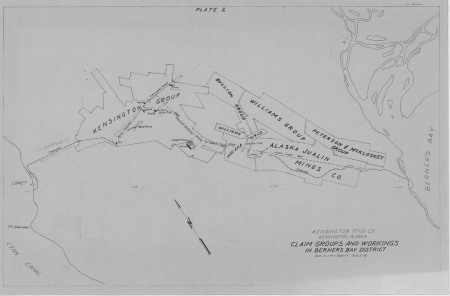

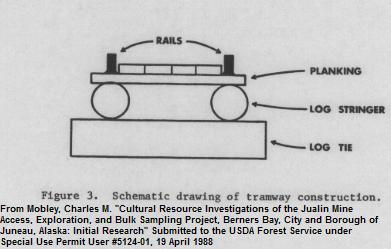

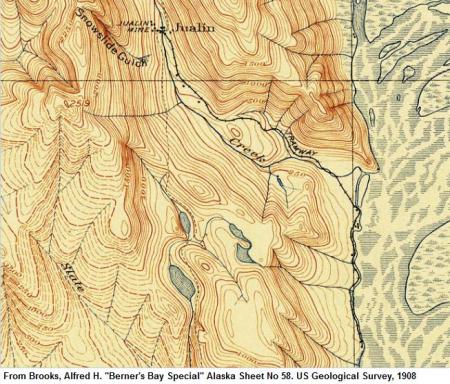

Berners Bay Mining & Milling Co Railroad

Cobol Tram

Goldwin Prospect Tram

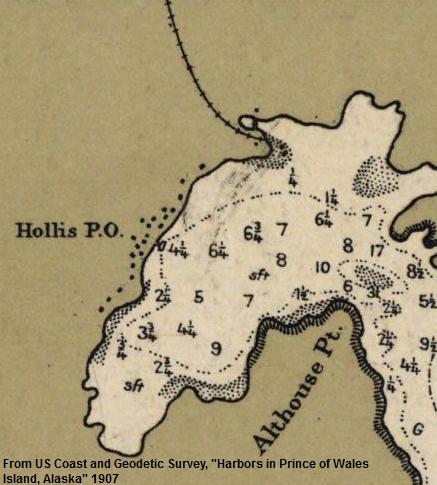

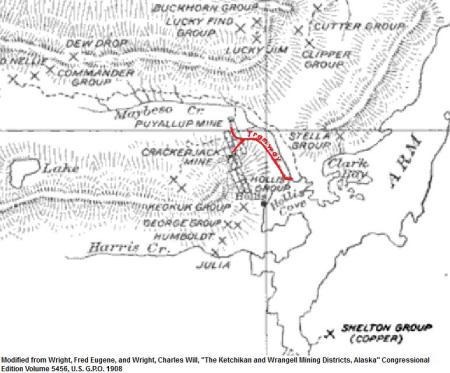

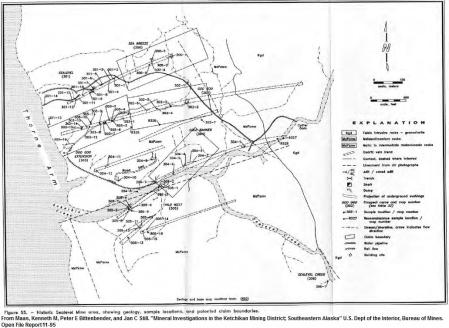

Hollis Tram

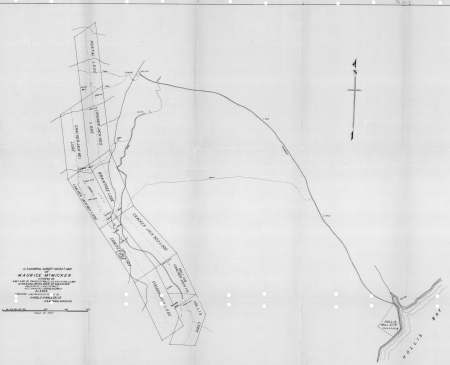

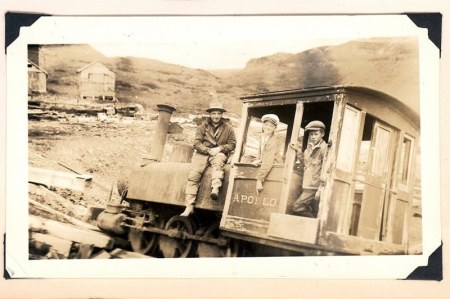

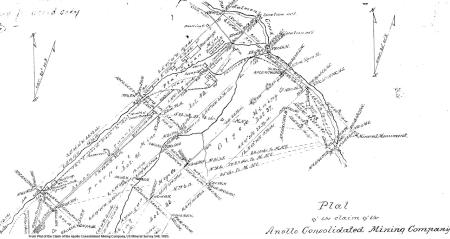

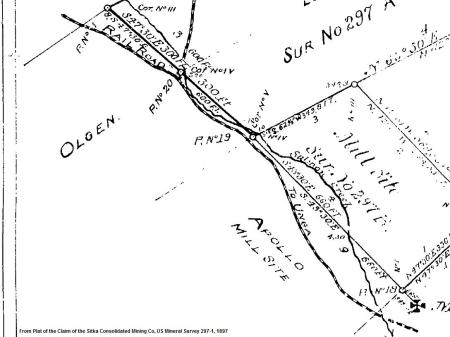

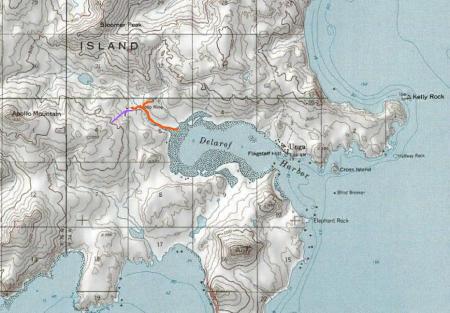

Apollo Consolidated Mining Co Railroad

Gold Standard Tram

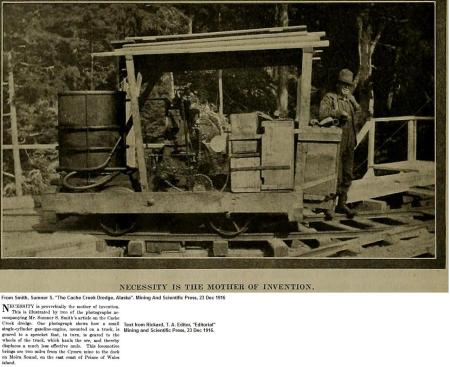

Cache Mine Tram

Sail Island Tram

It Mine Tram

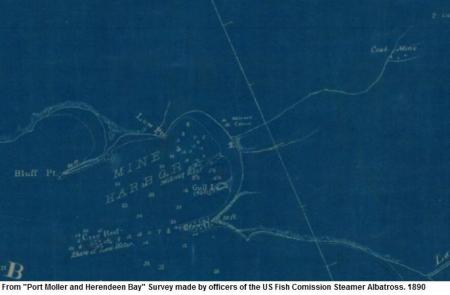

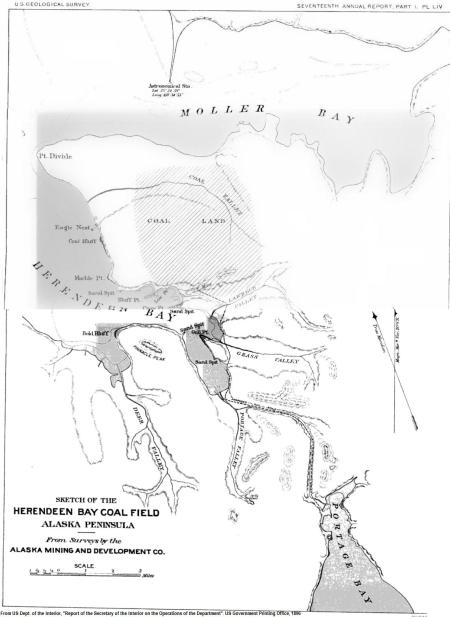

Herendeen Bay Railroad

William Henry Bay

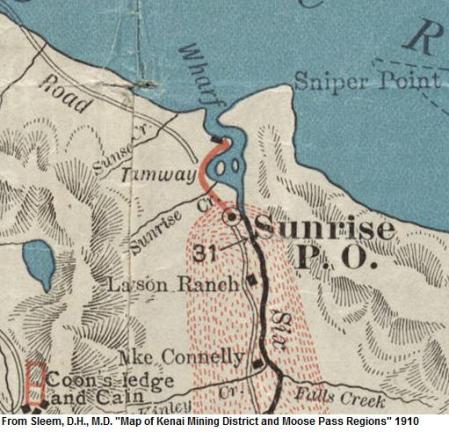

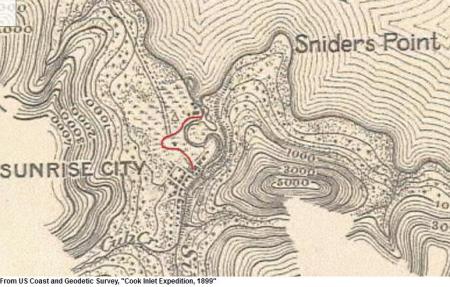

Sunrise Tram

Treasure Creek Incline

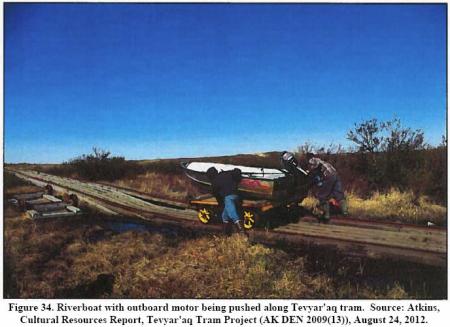

Yukon-Kuskokwim Portage

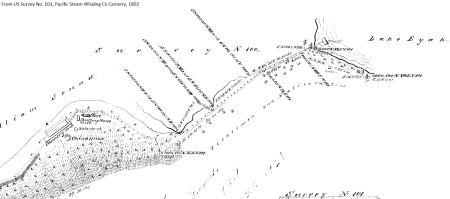

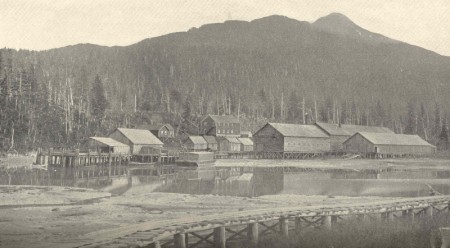

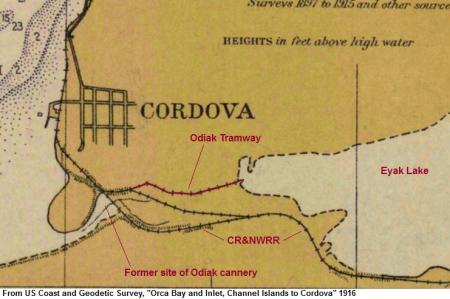

Eyak/Cordova Tramway

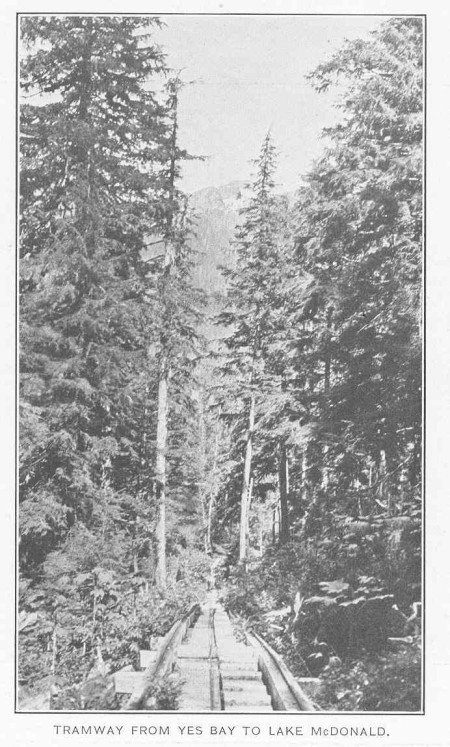

Yes Bay tram

Dyea Tramway

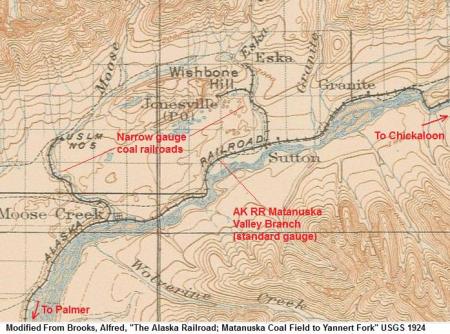

Matanuska Valley Branch Lines

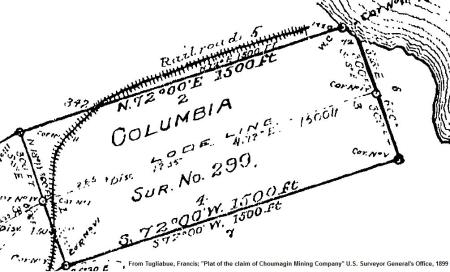

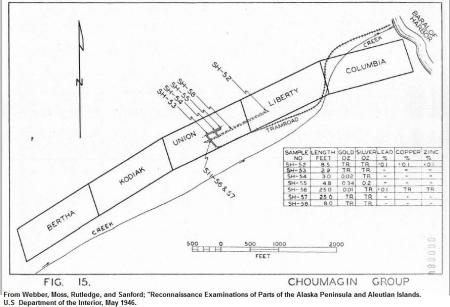

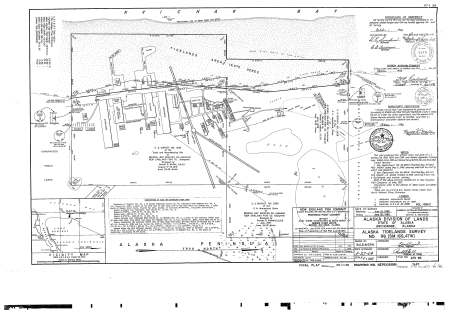

Shumagin Mine

Assorted Marine Ways

Chichagof Mine Tramways

St. Lawrence Island Tramway

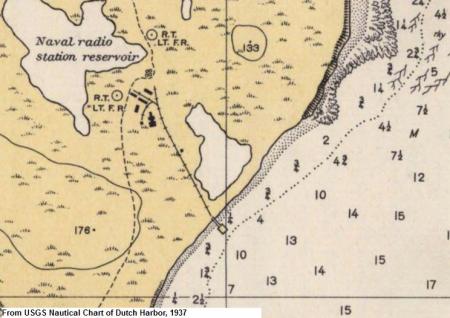

Dutch Harbor / Unalaska Tramways

Afognak Hatchery Tramway

Big Harbor Tramway

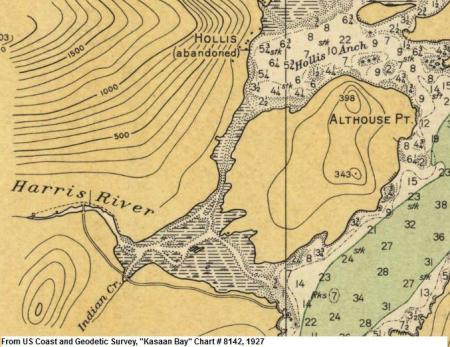

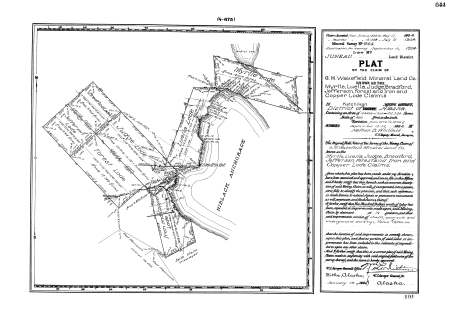

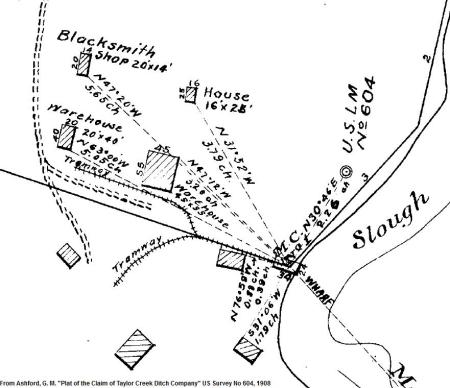

Harris River Tramway

Thorne Arm Tramways

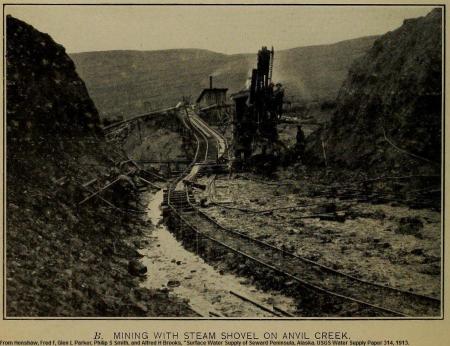

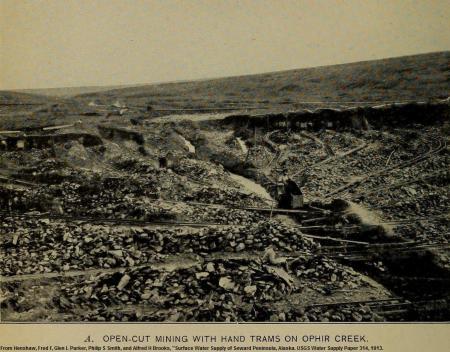

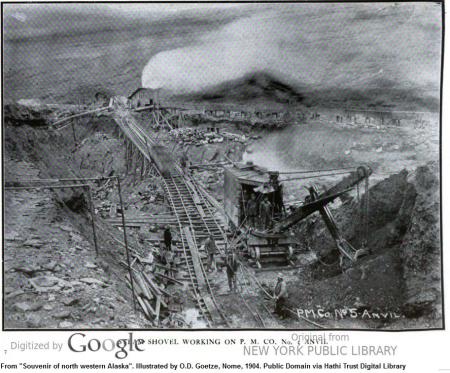

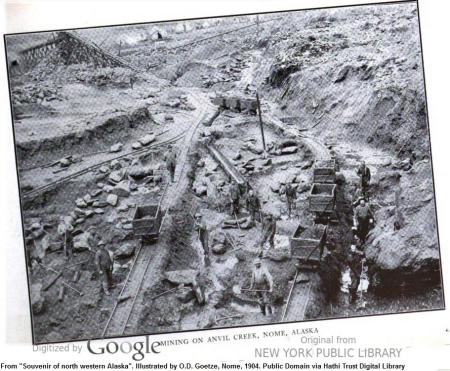

Nome Placer Tramways

Niblack Tramways

Davidson’s Landing Tram

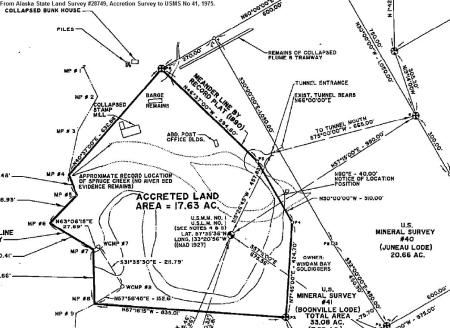

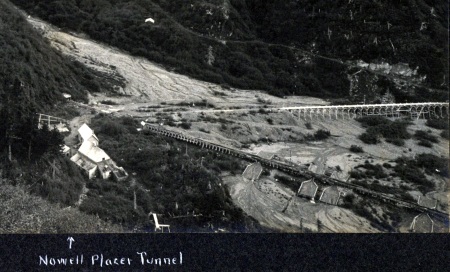

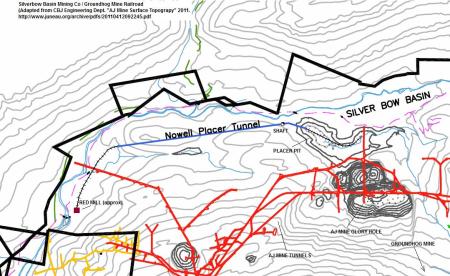

Silverbow Basin / Groundhog Mine Railroad

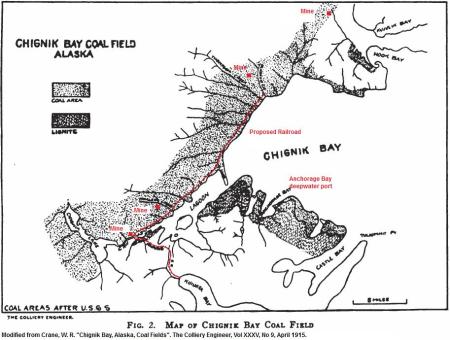

Chignik Railroad and Trams

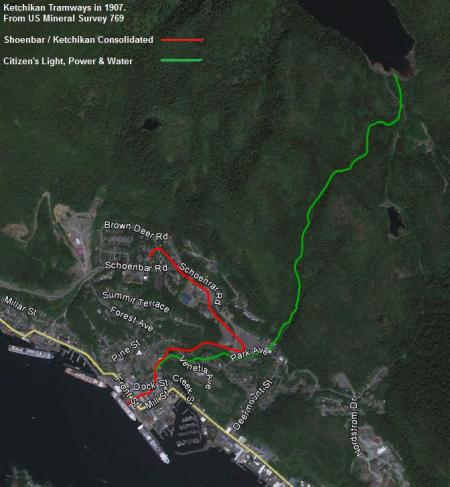

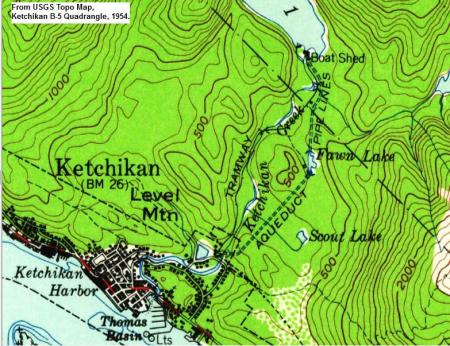

Ketchikan Creek Tramways

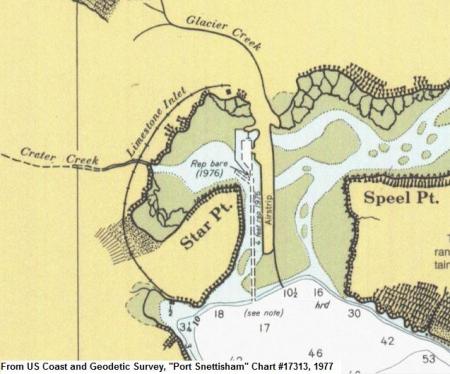

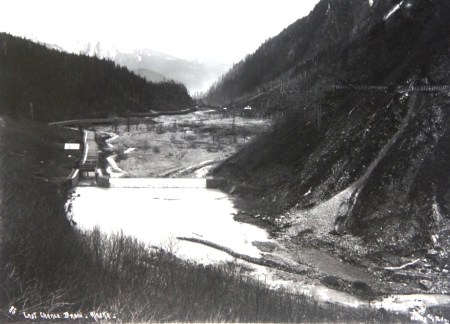

Speel River Project

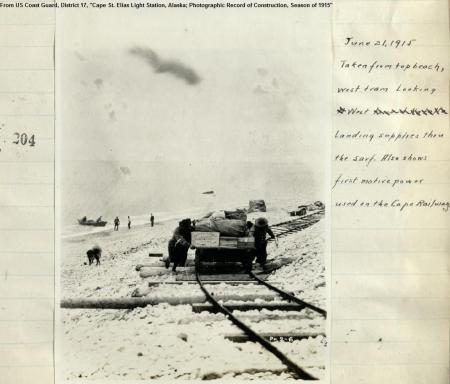

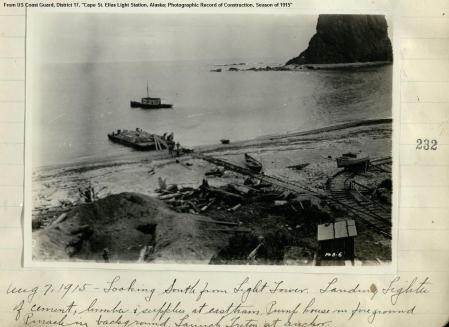

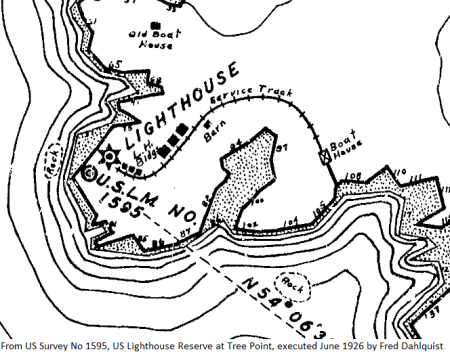

Various Lighthouse Tramways

Noatak River Tramway

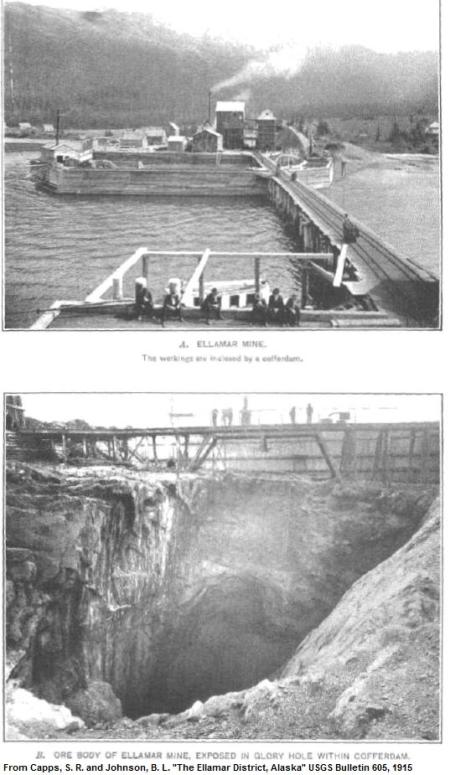

Ellamar Skipway

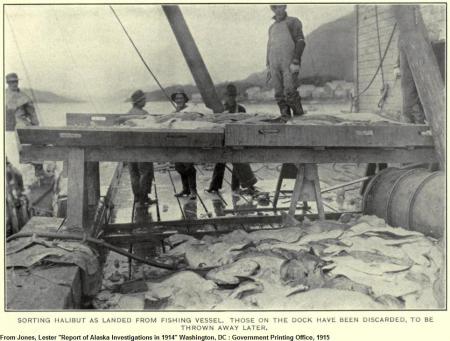

Various Fishing Industry Tramways

Koggiung Cannery Tramway

Salt Chuck Tramway

Bear Creek Tramway

St. Michael Tramways

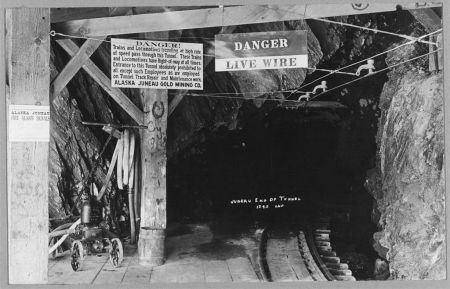

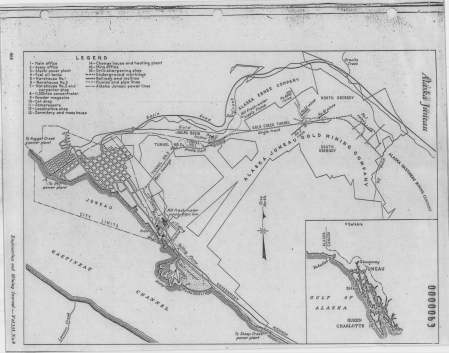

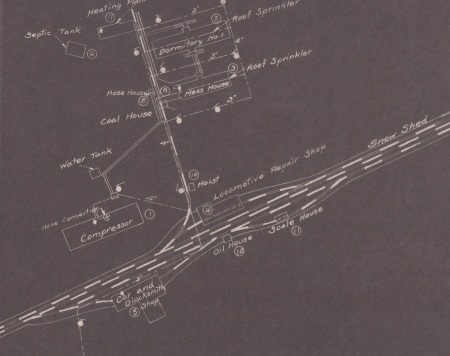

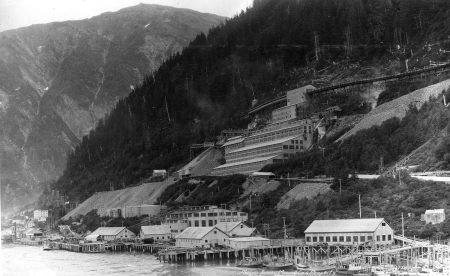

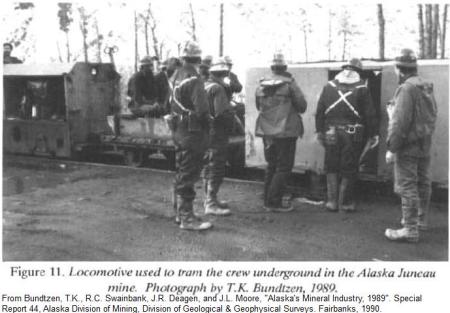

AJ Mine Railroad

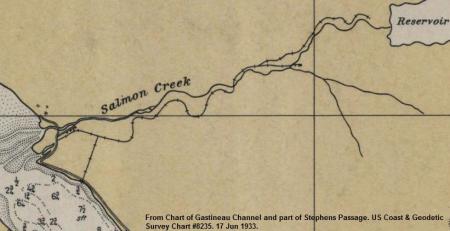

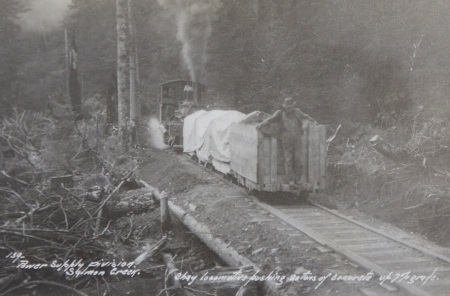

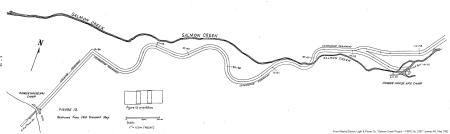

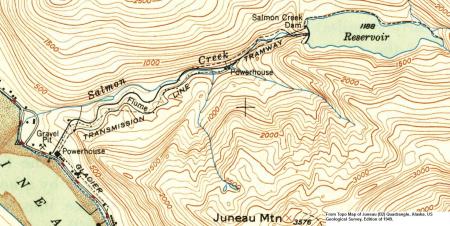

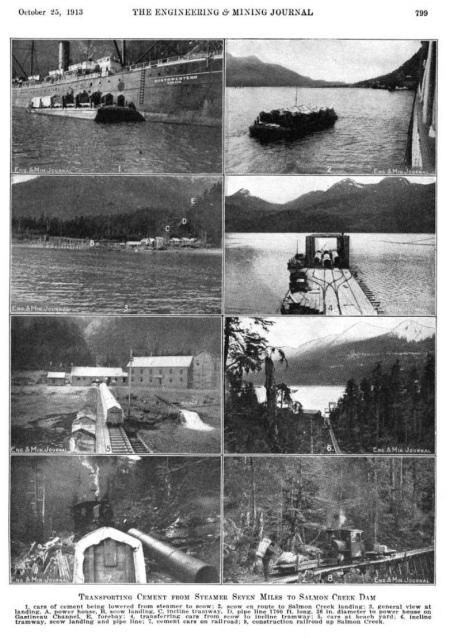

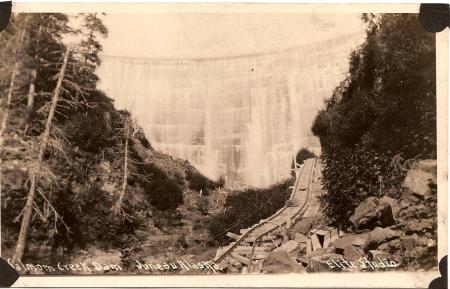

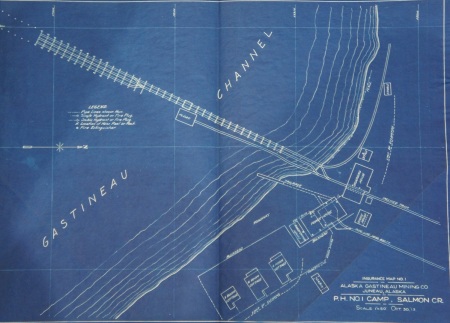

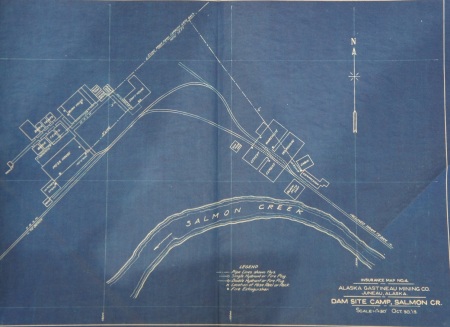

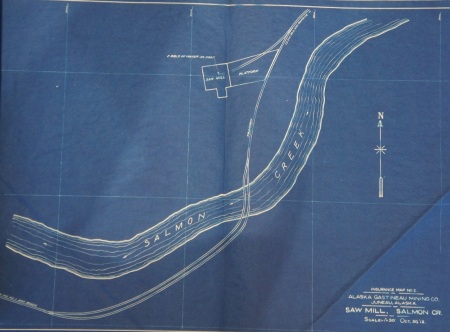

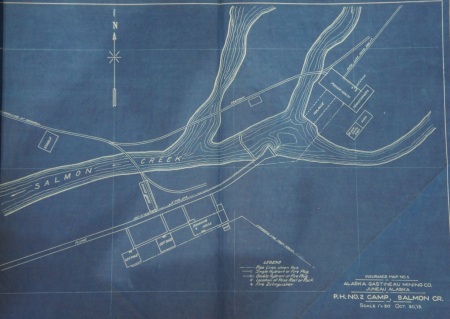

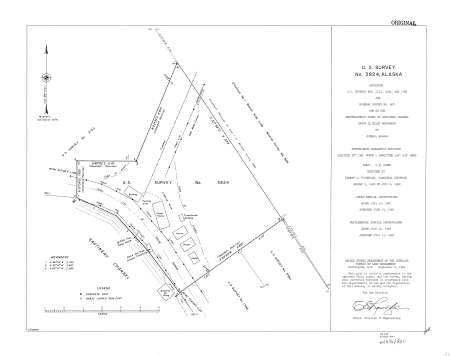

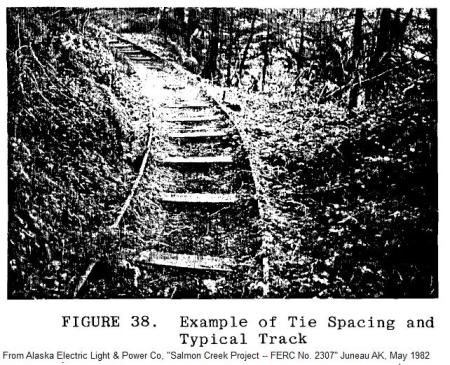

Salmon Creek Railroad

Annex Lake Railroad

Weeks Field Tramway

Esook Trading Post

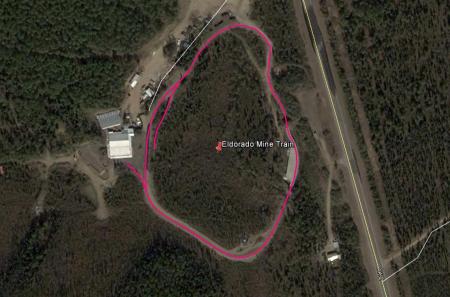

Fairbanks Tourist Railroads

Point Hope Tramway

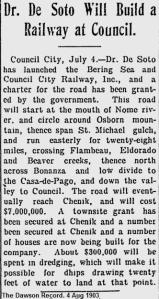

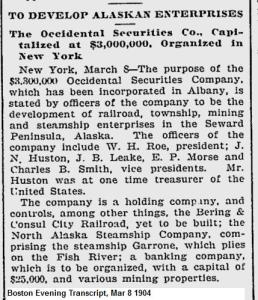

Bering Sea & Council City Railroad

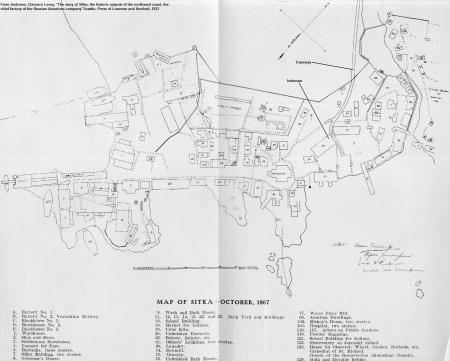

Sitka Coaling Station

Kenai Cannery Tramway

Nome Freight Tramways

Mammoth Creek Placer

Coal Harbor Tramway

Sitka Ice Tramway

Kodiak Ice Tramway

Culross Mine Tram

Sitka Lake Tramways

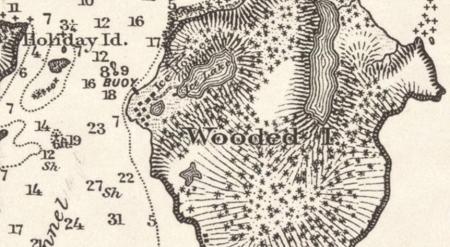

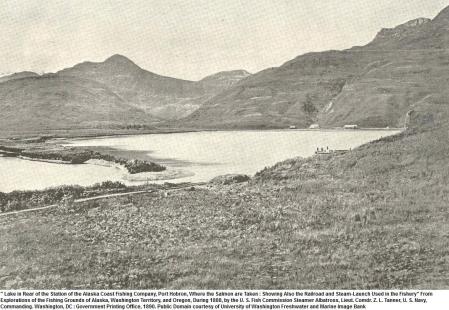

Port Hobron Tramway

Skagway & Lake Bennett Tramway Co

BIA School Trams

Alaska Treasure Tramway

Chitna-McCarthy Tramroad

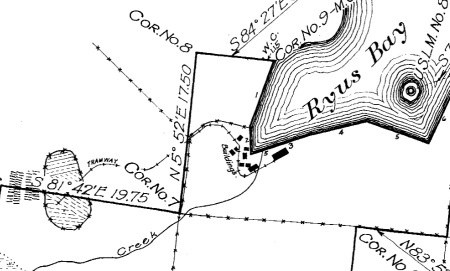

Ryus Bay Tramway

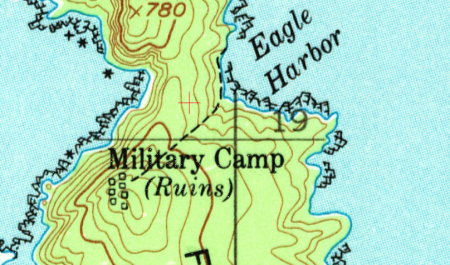

Fort Gibbon Tramway

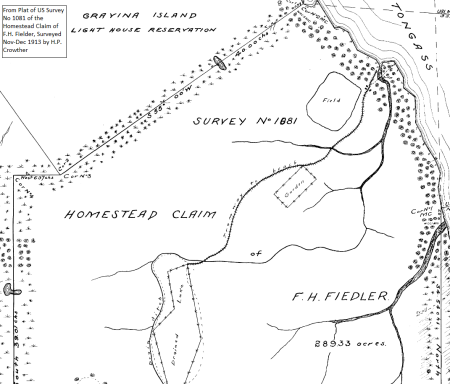

Gravina Island Tramway

Jualpa Flume Tramway

Unalga Island Tramway

Petersburg Wharf Tramway

Kotzebue Tramway

Coghlan Island Tramway

Dewey Lakes Tramway

Spike Island Tramway

Japanese Occupation Tramways

Payne Island Tramway

Girdwood Tram

Diamond Cannery Tram

Woody Island Naval Radio Station

Portland Canal Tramways

The inspiration for this page came while researching Funter Bay history. I came across a number of short line and mine railroads in Alaska that don’t seem to be well documented. Most official histories and rail fans tend to focus on the “big” lines such as the Alaska Railroad, the White Pass and Yukon, and the Copper River Northwestern. If they remember, some books and articles mention the midsize lines such as the Tanana Valley Railroad, the Yakutat & Southern, the tangle of railroads near Katalla, or the various lines of the Seward Peninsula. Unfortunately, many historians overlook the dozens of smaller operations that only ran a few miles, or only existed for a few years before folding. Such railroads are often well known to local residents but largely undocumented among outside historians and rail fans. Some histories also lump multiple railroads in one region together, especially around Katalla and the Seward Peninsula. This page is one good source that attempts to list as many railroads as possible. This page has quite a few collected photos and interviews. This page has a few photos from short lines in AK.

Often, the smaller rail lines were referred to as trams (or tramways, tramroads, tramlines, etc). This somewhat vague term can refer to anything from a human-powered or horse-drawn car on wooden rails, to an aerial cable-car, to a complete miniature railroad with locomotives, switches, yards, etc. Adding to the confusion, rail histories sometimes refer to the surface rail lines of small mines as “trams”, but to the mostly-underground lines of large operations like the Juneau mines as “railroads”. These terms mix interchangeably in historic documents.

Also confusing is the transient nature of the rolling stock, locomotives, and even the rails. Small lines often operated on a shoestring budget with recycled equipment (former streetcars from the lower 48 were popular). Tracks were frequently laid entirely on trestles rather than gravel grades, a cost-saving measure that meant the line completely vanished once the wood rotted away. Some lines were apparently built as investment scams and never intended to be permanent. When one railroad closed or went bankrupt, often another nearby line would buy or salvage the inventory, right down to the track. This can make it difficult to trace the origin and fate of equipment, or even verify the existence of certain operations.

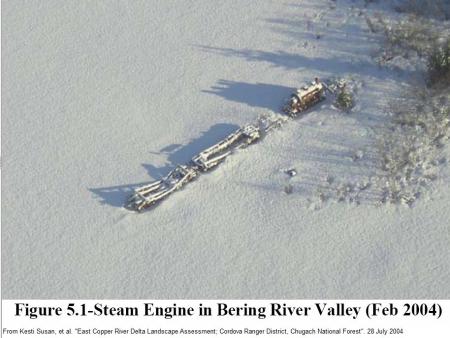

Alaska is a land so rich in rail history that you can still find abandoned steam locomotives just lying around. Here are a few. Here’s another one. Here’s another, and another.

This page is a work in progress, and will be updated as I find more information. I have tried to include only lines which actually operated or at least had significant construction. Railways which never got beyond preliminary planning are not detailed. In the case of animal or human-powered trams I have no fixed cut-off for size, but have generally limited myself to longer ones which led from a mine or industry to a dock, beach, or nearby town. This does not include the hundreds of *very* short tramways that typically led from mine adits to ore dumps.

I will try to provide references and documentation where available, but any errors are probably my own. If you have information or photos for any of the things listed here, or any that I’ve missed, please email me! I am happy to link to contributors’ websites or provide contact information if desired. If you would like to use any material from this page, please let me know.

________________________________________________________

Livengood Railroad / Tolovana Tram

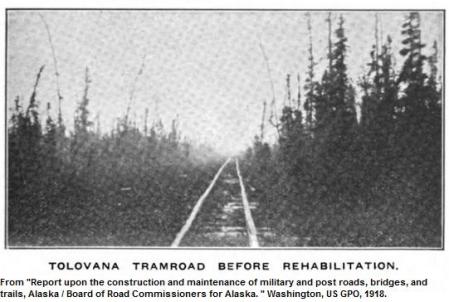

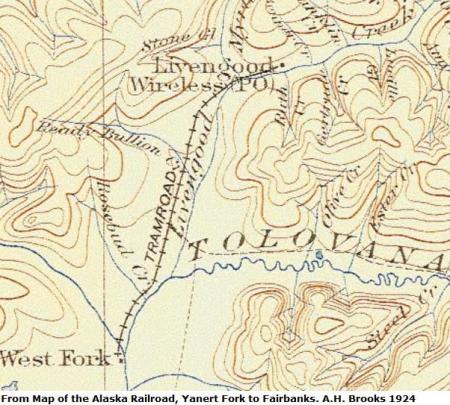

The Tolovana mining district near Livengood had a tram or railway, constructed around 1915. The line is often called the “Tolovana Tram”, although the territorial attorney general noted in 1921 that it was “a railroad in contemplation of law”.

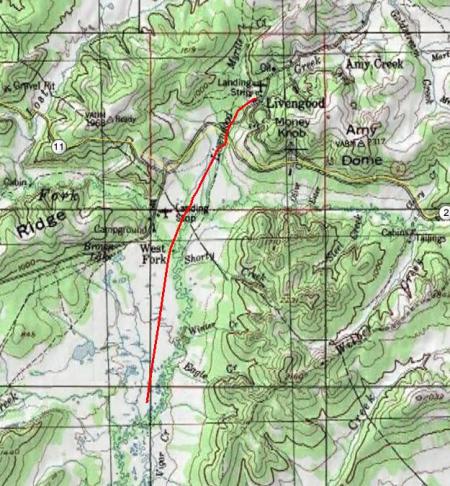

By 1917 the line was 6 miles long, running from the sawmill at West Fork to Brooks City (“the commercial center of the district”). Brooks City merged with Livengood around 1915, but in the early 1930s it was renamed back to Livengood to avoid confusion with other places named “Brooks”. The tramway was reportedly expanded to 15 miles by 1920, reaching the head of steamboat navigation on the Tolovana river at “Trapper’s Cabin”. The line later extended to “Log Jam”, an apparently dynamic phenomenon that was variously closer or farther from Livengood as the river and its debris shifted (details and documentation of the tram’s length and route are a bit sketchy).

Initially the motive power was a homemade steam locomotive, described below:

“From West Fork to Brooks a tram was under construction, wooden rails being used. A steam locomotive of crude construction is used to haul the cars which are also of local manufacture. The locomotive was constructed by putting a 20-horsepower boiler and a 5×8 double-cylinder hoist on a flat car, the gear of the hoist being connected to the axle by sprocket and chain. The cars were constructed from native lumber, the wheels being of wood with an iron rim and flange made from sheet iron.” (From “Report of the Mine Inspector for the Territory of Alaska to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1916”).

A photo from gearedsteam.com shows an example of such a homemade locomotive on wooden rails (not the one from Tolovana).

An article from 1915 lists local freight haulers Jules Marion and John Wigger (aka “Moose John”) as the tram’s builders. They applied for a 14-mile right-of way between Brooks and Trapper’s Cabin in November of that year, with the tram already under construction. Another article mentions Wigger and Chris Stadleman building a portage tram at the log jam in 1915. Falcon Joslin, the Tanana Valley Railroad’s founder, was reportedly interested in the tramway as well. In 1917 Charles W. Joynt of the TVRR was appointed manager of the Tolovana Tram.

A 1920 article named O.P. Gaustad as the tram’s owner, and mentioned that he had replaced the steam engine with a 1916 Dodge automobile on flanged wheels (other articles say that C.W. Joynt brought in one or more Dodge “locomotives” around 1917, and another article states that a Dodge and an Austin were both in use by 1919). Gaustad hauled six-ton loads from the steamboat landing to Livengood, as well as logs from his sawmill along the line. Gaustad also ran the post office and grocery store, and appears to have later become a territorial senator and editor of the Fairbanks paper. One of his partners in the Livengood area was A.C. Troseth. Another person involved around 1916 was David Cascaden, who seems to have built the sawmill prior to 1916 along with Julius Hoffman, Walter G. Fisher, and Jack H. McCord.

Examples of early Dodge automobiles converted into rail cars can be found at Goldfield, NV, and in California.

At various times, several shorter trams of 700, 1,300, and 2,000 feet (probably horse-drawn) were located at “Log Jam” and at “Trapper’s Cabin”. These allowed portage of freight around parts of the river blocked by frequent log jams. A 1982 report describes a wooden-rail portage tram at a large log jam 56 miles below west fork, and reports that Trappers Cabin was 16 miles downstream from West Fork (the exact distances and extent of the main tramway vary based on the source).

One of the smaller portage trams may have been built by Al Lien, as mentioned in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner of May 23, 1915. Another may have been built by Captain Sproul of the steamboat Martha Clow. He reportedly brought rails to “the log jam” in 1916 to build a portage tramway and haul the small steamer Livengood across for use upstream of the jam. A 1918 report mentions two portage trams around the log jam, one 1,600ft line owned by E.R. Peoples and the other of 2,200ft belonging to Marion & Thompson. A tram trip around the log jam cost $5 in 1918.

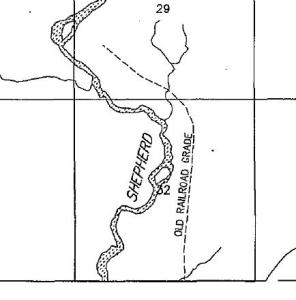

In 1924 the Livengood-Brooks tramway was sold to the Alaska Road Commission for $6,425, and the line required another $8,688.07 in repairs. Floods frequently washed away the tracks and damaged the grade. By the time the ARC took over, the line seems to have lost its last few miles from West Fork to Trapper’s Cabin, and was down to 13 miles. The Commission planned to extend the line another 12 miles to the latest “Log Jam”, eliminating two of the shorter portage tramways. The line was to be open to “Public use with gas cars”, similar to the Seward Peninsula Railroad (which was also called a tram after the road commission took it over). A survey from 1930 labels the Tolovana route as “Goverment (sic) Tramway” and describes it as 44″ wide.

The 1929 Road Commission budget allotted $20,000 in maintenance and repairs to the Tolovana line. Annual costs ran about $10,000 to $12,000. Despite the investment, some considered the line to be outdated and inconvenient. An article from 1929 described “the wooden tracked tram which winds its way over the low marshy ground”, and mentions that the track below Log Jam was “out of commission”. The article goes on to state that “The river and tram route never was practical and with the money that has been spent on it, a good road into the area could have been built”. Another article complained that the tracks were under water most of the year, and the tram could only operate for a few months each summer.

Around 1930 an old wagon trail from Olnes on the Tanana Valley Railroad was upgraded into a dirt road connecting Livengood with Fairbanks. This would later become the Elliot Highway. The complex and expensive river-and-rail route was no longer needed, and in 1931 the territorial legislature ceased operating the tramway. A bridge washout in July of that year ended public use of the line. A Fairbanks Daily News Miner article the following year advertised the remaining equipment and tracks for sale to the highest bidder.

The topo maps show a very straight “tractor trail” (possibly the tram grade) leading from Livengood past West Fork and into the flats to the South. Older topos show a “Sled Road” extending farther downstream and then cutting over towards Dunbar. A 1917 article claims that an extension of the tramway to Fairbanks was contemplated. After the planned extension to 25 miles in the 1920s, the line would have been only 30 miles from the Alaska Railroad siding at Dunbar. Recently the Alaska Railroad has considered building a Dunbar to Livengood spur, though not exactly along the route of the historic tram.

A government study mentions that “a tramway operated on the west fork of Olive Creek” near Livengood. It is not clear if this was a spur line or a completely separate tramway.

________________________________________________________

Treadwell Mines Railway.

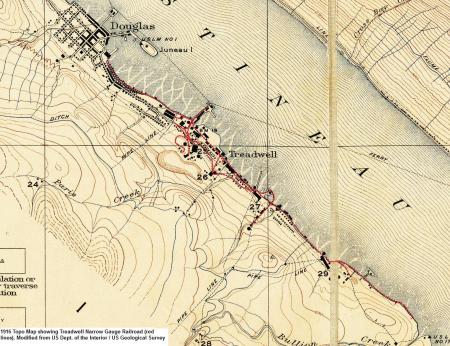

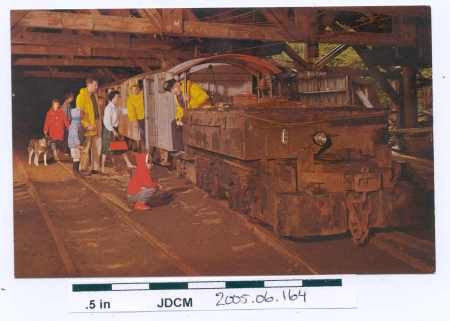

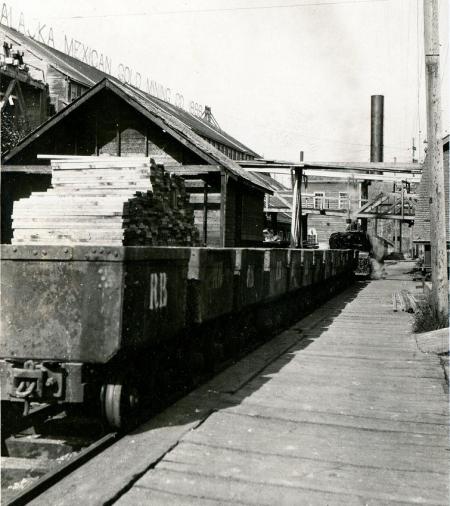

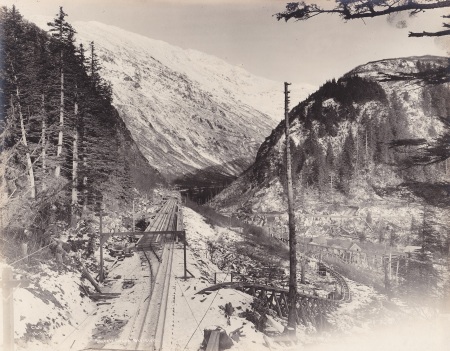

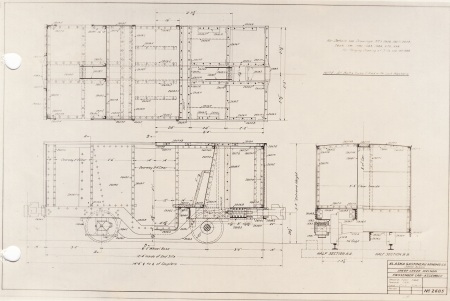

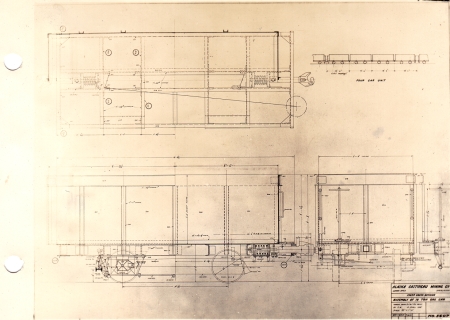

The Treadwell group of mines operated on Douglas Island across the channel from Juneau. The mines began around 1881 as a series of open pits (glory holes), and later excavated extensive tunnels below Gastineau Channel. A 25″-gauge surface railroad with several small steam locomotives ran between the mine buildings, mills, docks, and other facilities. Track also ran to the James Co sawmill in the town of Douglas and out to the powder magazine at Bullion Creek.

Around 1913 the railway began switching to electric locomotives, thanks to the cheap power made available by new dams. Underground operations initially used mules and horses to haul ore cars between the various mining faces and the central shaft. Underground tramming later used electric locomotives, although an interview with a miner described gasoline locomotives underground in 1915, with associated air-quality problems.

In 1917 most of the mine workings under Gastineau Channel collapsed and flooded. After the collapse, one mine in the Treadwell group was able to continue operations until about 1923. Most of the remaining buildings burned in 1926.

An overview of the Treadwell mine railroad in 1902:

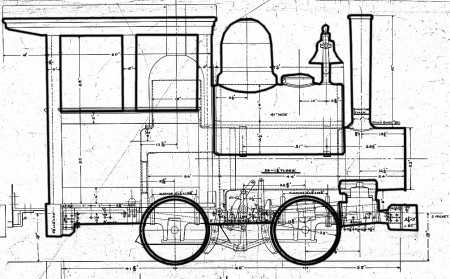

And a more detailed look at the peak of development in 1916, prior to the cave-in which destroyed most of the mines:

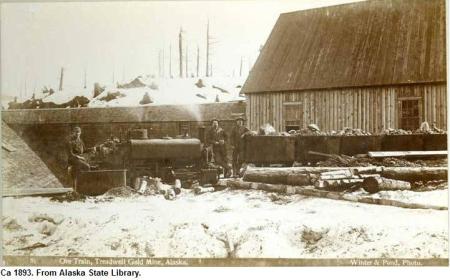

The original steam locomotives were of the contractor type, typically found in construction projects Down South. A photo of one of the Treadwell locomotives, dated ca 1893, is below:

Most photos show Treadwell’s locomotives with open cabs, which seems an oddity in rainy Southeast Alaska. Order sheets mention a “removable cab for summer use”, so it is possible the engineers found it too hot to operate with an enclosed cab in the summer. The photo below shows what one of these removable cabs looked like:

Courtesy of Alaska State Library, Robert N DeArmond Photograph Collection, PCA 258-862

One of the Treadwell locomotives (also with open cab) appears in Howard Clifford’s Rails North labeled as a WP&YRR switcher. This is most likely an error, as I have not found any other mention of such a locomotive at Skagway.

Below are some remaining 25″ tracks at the Treadwell mine site in 2002. This section seems to have three rails, the extra is probably a guard rail to keep the train from derailing on a tight turn.

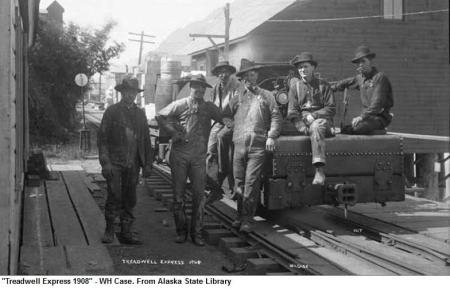

Another photo of one of Treadwell’s 0-4-0 steam locomotives, labeled the “Treadwell Express”:

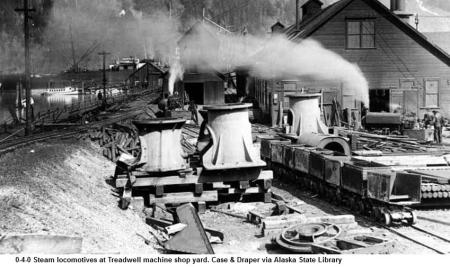

Three of these open-cab locomotives are seen below at the machine shop at Treadwell (all have steam plumes coming from them). Two have rounded saddle tanks (likely the Baldwins) and one has a flatter tank (likely one of the 1880s units). What might be the saddle tank of a 4th locomotive is behind the ore cars:

Close-up map of the wharf and machine shop area from 1910:

More detailed and complete maps can be found below:

Treadwell surface plant and railroads in 1910

Surface map overlaid on underground workings map, 1916

After the last shaft closed, most of Treadwell’s equipment was sold to the Alaska Gastineau Mine, then inherited by the Alaska Juneau mine. At least one steam locomotive was reportedly sold to the Funter Bay Mine. Other locomotives could have migrated to nearby mines after closure, or after the advent of electric haulage. Much of the remaining equipment and metal items were sold or scrapped after the mines shut down, but a small amount of track and at least one ore car remains on-site in the woods.

Several of Treadwell’s locomotives were built by the Baldwin company. A Baldwin 0-4-0 steam locomotive was ordered in 1896. A second Baldwin to identical specifications was ordered in 1897 and built in 1898. The paint scheme was to have been olive green and aluminum. Fuel was originally to be bituminous coal, although documents and photos indicate that the locomotives were later switched to oil.

“In conjunction with the Alaska United Gold Mining Company, there was bought a new Baldwin locomotive to replace the one blown to pieces in the dynamite explosion of last spring ” (1897 Report of the Governor of Alaska to the Secretary of the Interior).

The mine suffered several dynamite accidents in the spring of 1896. In April, four tons of powder in the magazine detonated, killing a watchman . In March, a train struck dynamite lying on the track, sending pieces of the engine and cars flying through nearby houses. An early report indicated the explosive had fallen from a previous train, and claimed the blast killed a woman and child nearby. A later article said no one was killed, and blamed the accident on a local native who was injured in the blast.

Dynamite flatcar at a magazine tunnel, possibly at Treadwell:

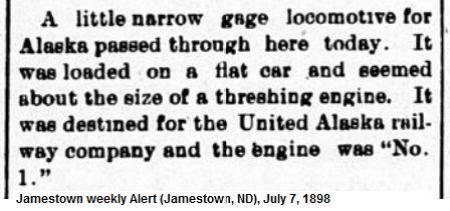

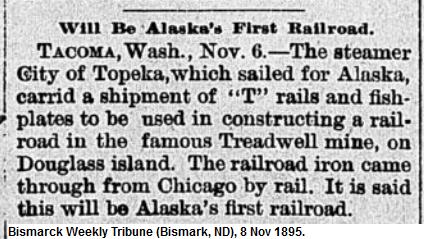

The 1898 locomotive was described briefly in a North Dakota newspaper on its way to Alaska:

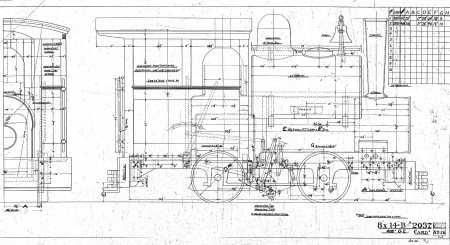

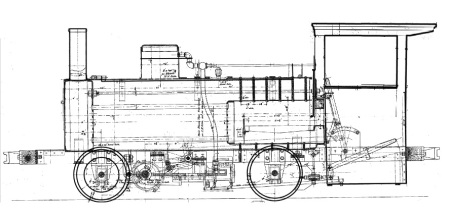

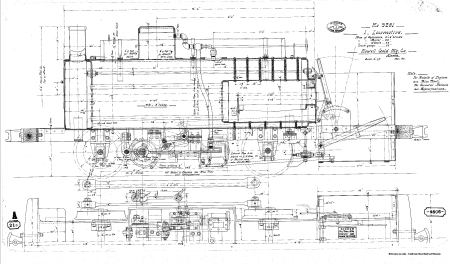

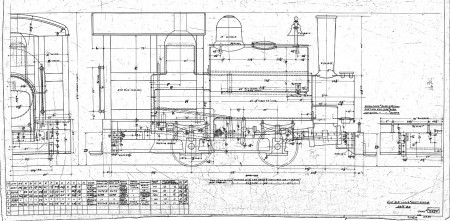

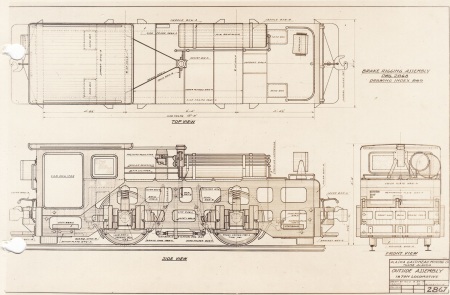

Both Baldwin locomotives were class 4-11 C, saddle tank engines commonly found in construction, switch yards, and industrial operations. A diagram of this type (with cab) is seen below:

A close-up of what appears to be a Baldwin locomotive with open cab is seen on the Treadwell wharf below:

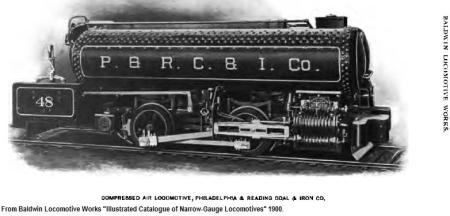

Baldwin also built a compressed air or “fireless” locomotive for Treadwell in 1900. This is mentioned in the index of Erecting Drawings as index 5000A-95, Tracing # 7038. It was possibly used underground or somewhere that open flame was not desirable (such as the explosives magazine).

Example Baldwin fireless locomotive from 1900 catalog:

A 1922 publication describes 2,600 tons of ore hauled per day by compressed air locomotive at the Alaska Treadwell Mine. In addition to the Baldwin, several Rix & Firth pneumatic locomotives seem to have been owned by the Treadwell company. These were described as very small units, possibly for handling ore cars in tight side drifts where the slightly larger haul locomotives would not fit. An 1887 publication mentions a Phoenix Iron Works pneumatic locomotive shipped to Douglas Island for surface use.

Various locations in Alaska claim to have had the first railroad in the state, including Seward City (Comet), Skagway, Homer, Cordova, and Seward. While the White Pass & Yukon probably has a valid argument for the first common carrier in 1898, the following articles seem to indicate that Douglas Island had the first steam locomotive in Alaska (actually, at least the first three):

Juneau Alaska Free Press, Aug 11 1888, Page 3, Col 3: Locomotive arrived for the AM&M Co (Mexican Mine) on the steamer Ancon.

1889 Juneau Alaska Free Press: “The first railroad in Alaska” at Douglas, with another locomotive delivered that year by the steamship Geo W Elder. This may have been the same one mentioned on June 8, 1889; delivered to the Bear’s Nest Company (a mine adjacent to the Treadwell group and under the same management).

Juneau Alaska Free Press, April 13, 1889, Page 3, Column 5: Another locomotive shipped to the A. M. & M. Co on the steamship Corona. Locomotive was named “Douglas Island”.

Another article claiming that “Douglass island”(sic) had the first railroad in Alaska came out in 1895. It does not mention the earlier locomotives delivered in 1888 and 1889.

There also seem to have been a number of compressed air locomotives at the Douglas Island mines as early as 1887.

Later sources mention electric and gasoline locomotives used at Treadwell on the surface tracks. There were also storage battery locomotives used underground. Some of the gas locomotives are listed as 30″ gauge. These could have been converted to Treadwell’s 25″ surface gauge, used in an underground haul tunnel with wider track, or used at off-site rail lines such as the Nugget Creek powerplant.

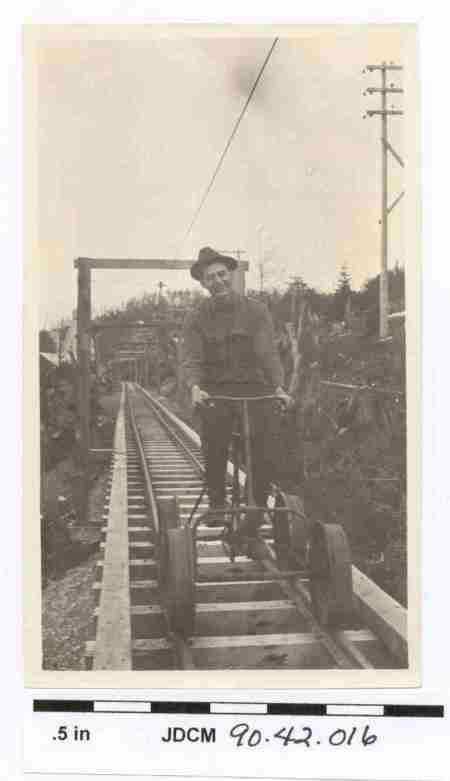

Another interesting rail vehicle seen in several Treadwell photos is a type of rail bike, aka a “velocipede” or “light inspection car” (seen at right in this photo, ridden by the man in the white boater hat). These were essentially bicycles with 4 flanged wheels. An 1898 advertisement can be seen here. A preserved museum specimen can be seen here. Another of these bikes at Treadwell is seen below. This was after electrification of the surface track, the overhead power wire is visible:

Hank Graybill, Treadwell, Alaska, c. 1917. Image courtesy of the Juneau-Douglas City Museum, 90.42.016.

A newspaper report from 1902 relates how engineer John Laughlin left his locomotive (Treadwell #1) parked at the Douglas sawmill during his dinner break, as he had done for the last 5 years without issue. On this occasion, a young man named Riley decided to take it for a joyride. The locomotive gained so much speed that Riley became frightened and leaped off, leaving the engine to crash through a coal shed and land on the beach. It was reportedly undamaged but the tender trucks were broken.

Partial locomotive roster for Treadwell Mines Railroad

(in progress):

Steam:

-1888 steam(?) locomotive. Maker unknown.

-1889 steam(?) locomotive. Maker unknown. Possibly for Bear’s Nest Mine.

-1889 steam locomotive. Maker unknown. Named “Douglas Island”. Possibly with flat-topped saddle tank.

-1896 Baldwin 0-4-0 steam locomotive. Construction No 14823. 9×12 cylinders. Named “Mexican”, tank marked “A.M.G.M. Co #1”.

-1898 Baldwin 0-4-0 steam locomotive, CN 15988. 9×12 cylinders. Tank marked “Alaska United #1”.

-??? Davenport Locomotive Works 0-4-0 (reported, no documentation found to date).

Compressed Air:

-1900 Baldwin Locomotive Works

-1887 Rix & Firth 0-4-0 (and possibly another Rix & Firth from 1889) Per John Taubeneck and mentioned here.

-1887 Phoenix Pneumatic

Electric:

-1913 GE 500V DC trolley-type, 6-ton.

-1913 GE 500V DC trolley-type, 6-ton.

-1914 Baldwin battery-type, 30″ gauge

-1914-1916 Baldwin battery-type, 25″ gauge (several units)

-1915 Westinghouse-Baldwin battery type, 4.5-ton. Marked “A.T.G.M. Co #56”.

-1915 Westinghouse-Baldwin battery type, 4.5-ton.

-1915 Westinghouse DC trolley-type, 8-ton.

Gasoline:

-1913 Whitcomb DD engine, 4-ton. 25″ gauge, #210

-1913 Whitcomb DD engine, 4-ton. 25″ gauge, #262

-1913 Whitcomb F engine, 8-ton. 30″ gauge, #278

-1914 Whitcomb F engine, 8-ton. 30″ gauge, #334

(gas locomotive information courtesy of John Taubeneck)

________________________________________________________

Cook Inlet Coal Fields Railroad

“Locomotive with steel tank on flat freight car”, c. 1897-1940. Image courtesy of the Juneau-Douglas City Museum, 2009.36.098

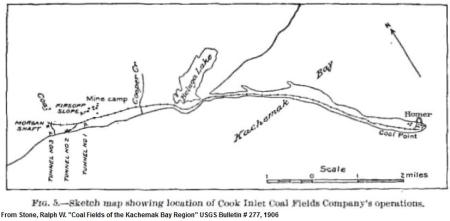

The Cook Inlet Coal Fields Company opened a mine in 1899 at Homer, AK. From 1900-1903, one or more small steam locomotives ran on an 8.5 mile, 42″ narrow gauge track from the mines to the end of the Homer spit. This gauge (sometimes called “Cape Gauge”) was used in several railroads in Alaska. It was also used in various municipal street railways in the lower 48, and became something of a standard in American coal mines by the 1920s (ref).

The locomotive pictured above appears to be taking on water from a stream near the mining camp. The photo was found in the Juneau Douglas City Museum archives, the background scenery more closely match Kachemak Bay than any of the Juneau-area railways. Very faint lettering on the saddle tank may include the word “Inlet”. The activity pictured would also make sense for Homer. As the original center of Homer was on a sand spit several miles from the nearest stream, the homemade tank car likely transported fresh water back to town.

A 1901 court case against the Cook Inlet Coal Fields Co mentioned that “A number of the rails were old second-hand rails, to wit, had been used in street-car tracks” and that “The cars were old, discarded street-cars… trucks that they used to use in Seattle on the old horse-car lines.” (specifically mentioned is the James Street line, a 42″ gauge cable and horse trolley line which was electrified around 1899). The rails were bought from the W.D. Hoffens firm at $35/ton.

The locomotive is described as a newly-built “Port & Son” (H.K. Porter) ten-ton engine. John Taubeneck’s information lists this as Construction Number 2037, 8×14 cylinders, 0-4-0ST. Porter records state it was ordered in May of 1899 and shipped disassembled “for export”. Railroad equipment was shipped to Homer in September of 1899. The locomotive was “set up” and track laying began on June 23, 1900.

Elevation Drawing for locomotive 2037. H.K. Porter Co, ca 1899. Courtesy of Canada Science and Technology Museum.

The Cook Inlet Coal Co was incorporated under the laws of West Virginia, but was apparently based in Philadelphia. President of the company was Captain Alfred Ray, VP was Edward Anderson Ryon, and Secretary Treasurer was Clarence Eugene Lent. Other stockholders included A.N and A.S. Chandler, and W.B. Addison. Initial authorized capital was $1,650,000.

An investment article in 1901 claimed that the company had spent most of their efforts developing the railway, dock, and a sawmill, and had not yet begun to mine coal extensively. The quantity of coal was claimed to be “unlimited”. A.S. Chandler & Co of Philadelphia had taken a first mortgage of 6% gold bonds on the property. The company’s officers were described as “Philadelphia business men of high standing and means”.

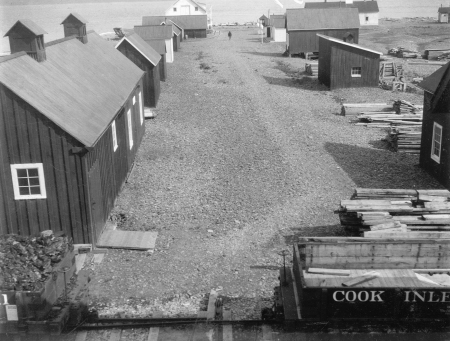

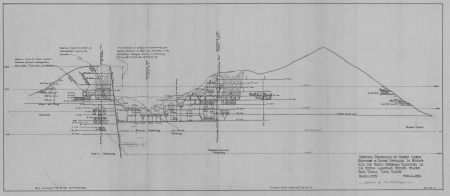

Homer townsite, wharf, and railroad shops around 1904:

Despite the “unlimited” quantities of coal, the quality proved lower than that available from California and Washington State. While suitable for heating, the coal had only 70% of the fuel value of competing deposits, and was not efficient for the steamship market. The Russians had discovered this as early as 1856 when they attempted to use Kachemak Bay coal in their steamers.

By some accounts, the mines and railway ceased operation in 1902 or 1903, with the last loaded train left to sit for several years. On Sept 7, 1904, West Virginia creditors petitioned to have the company put into involuntary bankruptcy. An article from the Homer Tribune notes a 1905 bankruptcy sale, indicating that there were two locomotives worth $3,000. Howard Clifford also mentions a 2nd locomotive listed in the Marshall’s sale. Other property auctioned off included ten coal cars, five old street cars, and various livestock. Despite appeals by the company, the bankruptcy was upheld.

Rail cars loaded with coal at Homer are seen below. Two empty cars are in the distance.

The railway may have seen some use after bankruptcy, as some of the investors attempted to retain control of the coal deposit. The Michigan-Alaska development company, also known as the McAlpine, Mackey, and Bushnell groups, purchased the railroad and the town of Homer in 1906 and 1907 (some of these same people seem to have been involved as early as 1900). They soon faced conspiracy charges in Federal court relating to the re-staking of claims in the area. Supposedly the new company had solicited hundreds of Detroit residents to file mining claims on their behalf, in order to side-step new Federal restrictions.

Barred from mining coal, the Michigan-Alaska syndicate began scrapping equipment in 1912. The rails were removed around 1913, and salvage firms shipped more equipment to Seattle between 1913 and 1915. Some of this salvage work resulted in further court cases. Locomotive 2037 was reportedly shipped back to Seattle by the Miller Machinery Co around 1913.

At least one newspaper article paints a picture of deliberate scandal and fraud around the operation, claiming that the entire town of Homer had been built as a sort of Potempkin village:

“BUILT FAKE TOWN TO GET PICTURES AND SELL STOCK … This company sent north, the government charges, a number of grading engines, dump cars, and street cars and built the uninhabited town of Homer, with saloons, dance halls, hotels, etc, in order that pictures might be taken for the prospectus used by sellers of stock. The machinery and other relics were brought to Seattle last week and the “town” is now entirely abandoned.” From Meriden Morning Record, 5 Dec 1913

The photo below might be one of the aforementioned pictures, showing “Downtown” Homer with loaded and empty coal cars in the foreground. Rails are also visible in the distance curving around the last several buildings.

Public Domain photo courtesy of USGS Photographic Library

A photo showing some of the rails on the dock is here.

Another photo of the railway yard is here.

A visitor to Homer in 1910 reported “roundhouses, machine-shops, engines and cars”… the fourth source to suggest multiple locomotives on the railroad. The identity and fate of any additional locomotive(s) is not known. Some of the rolling stock seen in photos is larger than that normally handled by small 0-4-0 switchers. It is possible the company owned or planned to buy a larger locomotive for regular hauling after the Porter was finished with track construction.

Other coal mines operated in the area during the late 20th century. The Cook Inlet Coal Fields Co had planned to expand their railroad to several other mines around Homer, including Moose Station and Coal Creek. In 1894 the North Pacific Mining and Transportation Company operated a tram 1/2 mile from the shore to a mine in Eastland Canyon, about 14 miles northeast of Homer. An 1892 article mentioned that the Alaska Coal Co planned to build a “tram railway” in the area that year.

Coal deposits near Homer are occasionally examined for renewed development. At least one project in the 1950s proposed to use local coal for power plants. The area also experiences occasional coal fires.

________________________________________________________

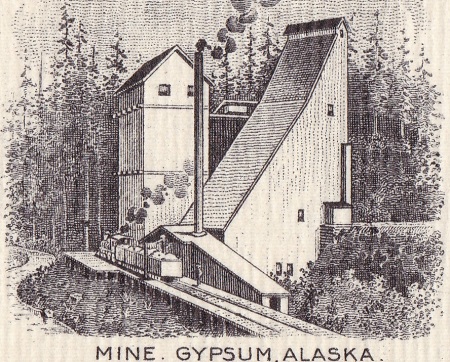

Pacific Coast Gypsum Company Railroad

Part of Pacific Coast Gypsum Co letterhead. Courtesy of Alaska State Archives, Letterhead designs etc., Alaska businesses, ca. 1890-1933, MS 43.

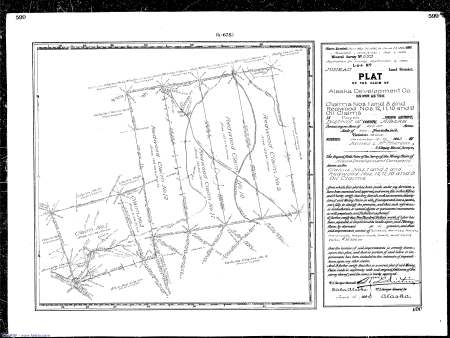

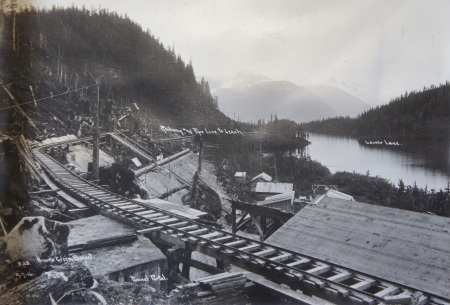

The mining town of Gypsum was located at Iyoukeen cove on Chichagof Island. Gypsum rock was mined from about 1902-1923 by the Pacific Coast Gypsum Co of Tacoma. A wharf extended 2,000ft into the cove and a steam railroad ran from this wharf to the shaft headframe about 1 mile inland.

Below is the first wharf in 1912, prior to its collapse. The view is looking down the incline from the ore bunkers towards the shore. The track on the right runs level alongside the incline for dockside loading:

Raw gypsum was shipped to the company’s reduction plant at Tacoma where it was prepared for wallboard and plaster use. The Tacoma wharf can be seen on the right in this photo.

The deposit was reportedly discovered in 1901 by a Mr. Rhinehart of Tacoma. By 1902 a bunkhouse and blacksmith shop were completed and a roadbed had been cleared from the beach to the shafts and tunnels along Gypsum Creek. President of the company was William R. Nichols, and VP was Sidney Albert Perkins. General managers at various times included J. A. Siefert and Albert G Mosier.

This railway used at least one small saddle-tank locomotive which looks a bit like the ones used at Treadwell. It is likely another contractor-type dinky. Railroad historian John Taubeneck supplied this information on the line, found in the May 1st, 1909 issue of Pacific Builder & Engineer:

Pacific Coast Gypsum

(6) 5-ton cars

(1) 12-ton Porter locomotive

Cars & locomotive furnished by Phillips, Morrison & Co. Seattle, WA

36″ gauge with 30# rail

total track 6500′

grade to cargo bunkers 2%, grade to mine 1 1/2 %

As seen in the background of the photo below, the ore bunkers were set high on the wharf to allow gravity loading of ships, and the track to the bunkers runs up a ramp or trestle from the pier. Such docks existed at several mines in Alaska, they followed the pattern of larger ore docks on the Great Lakes, but at a smaller size. A great scale model of such a small ore dock can be seen here.

Gypsum locomotive in 1918 on the second wharf:

A photo of an ore car backed up to the headframe is seen here.

A photo of gypsum being loaded into a mine cart from a stope is here.

A gypsum outcropping and cave spring can be seen here.

Some present-day views of the area are here.

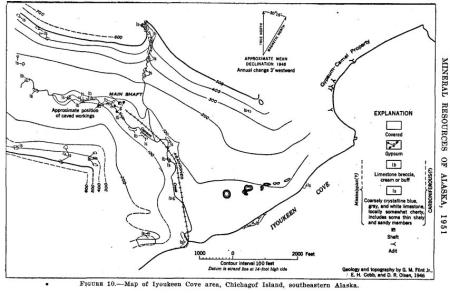

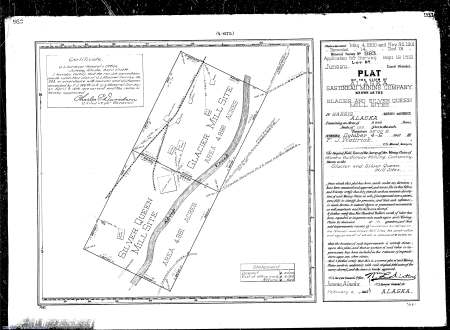

Map of the railway from shaft to the beach (wharf not shown):

The railroad is described as follows in 1906:

The mine operated for two decades despite various problems, including a collapsed dock in 1912, a fire in 1918, occasional barge accidents, and ongoing issues with water. One flood in 1919 required divers to descend the shafts and secure steam pumps located underground (source). The shaft reached well below sea level, and some accounts say that the tunnels broke through into natural caves and voids in the soft gypsum. This allowed groundwater to flow in (natural sinkholes and springs nearby indicate caves in the area). In 1921 the pumps were reportedly handling a flow of 1000 gallons per minute into the mine. The operation ceased around 1923, citing a lack of easily-accessible gypsum and the expense of keeping the mine pumped out (coal was imported from Washington State to run the pumps).

After closing, a locomotive was left parked on the tracks alongside Gypsum creek. Duane Ericson located the locomotive on its side in the creekbed where the grade had washed out. More of his photos and description are here and here.

Interestingly, the locomotive shown above may not have been the only, or the original, locomotive used at Gypsum. Accounts vary, but one of Gypsum’s locomotives may be at the bottom of Milbanke Sound in British Columbia. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s wreck tables say that 2000 tons of gypsum and “a locomotive for Tacoma” (possibly being sent out for repairs) were on board the Alaska Barge Co’s James Drummond, southbound from Gypsum, when she ran aground and sank in October of 1914. Although the crew was taken off and the barge appears partly above the water in various photos (photo 1 and photo 2), efforts to refloat it were unsuccessful and the barge was a “total loss”. This page notes that Canadian authorities would not allow American vessels to do the salvage work before the barge fully sank. However, this article claims that machinery loaded on the deck was saved, possibly including the locomotive.

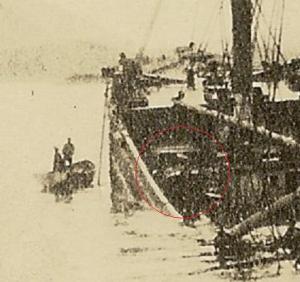

Possible saddle tank locomotive as deck cargo on the James Drummond wreck:

Adam DiPietro sent me some additional photos that further support the idea of a 2nd locomotive. The one resting in Gypsum Creek appears to have slightly different

________________________________________________________

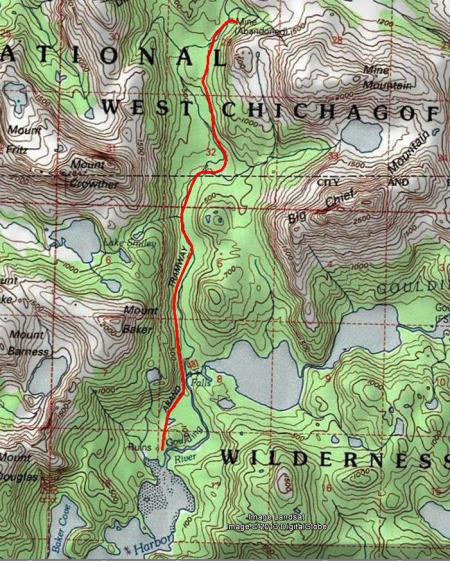

Pinta Bay / Goulding Harbor Railroad

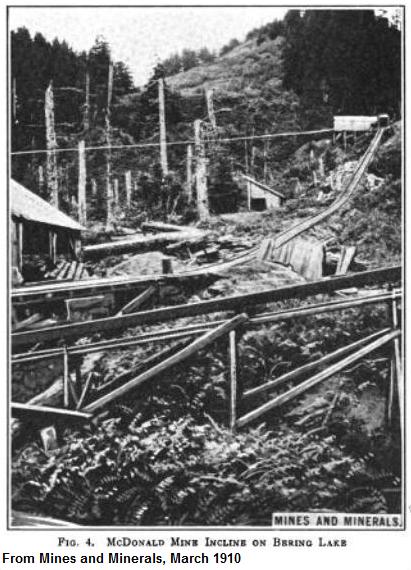

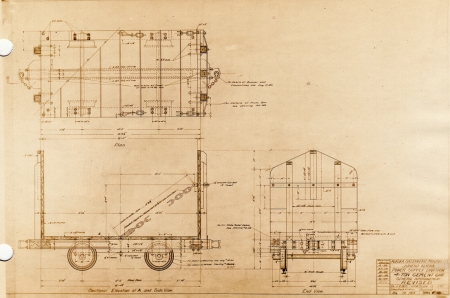

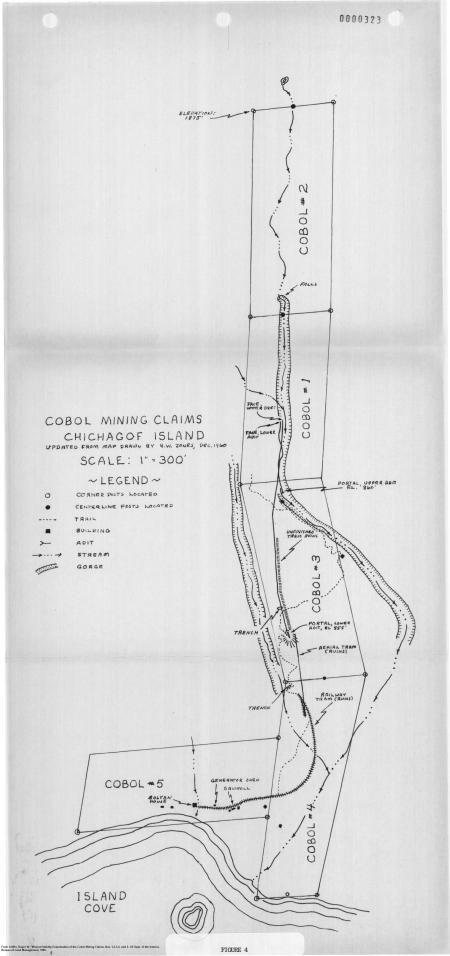

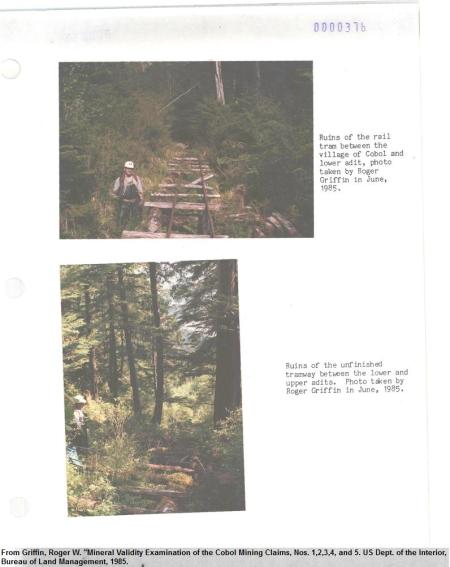

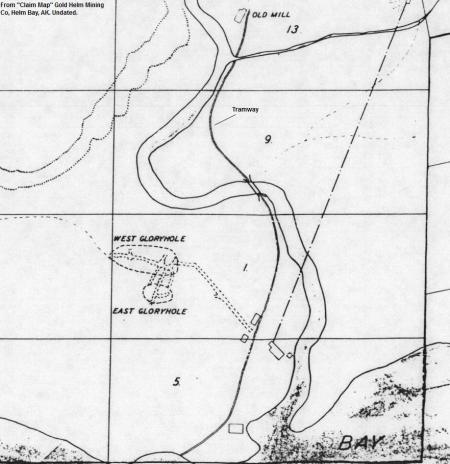

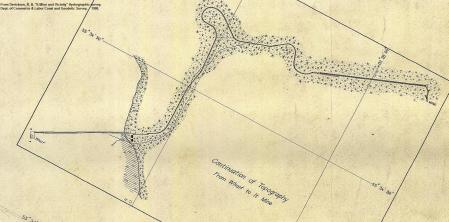

The Pinta Bay Mining Company at Goulding Harbor operated a rail tramway about 5 miles long. This led from the shore along the Goulding River to the Cobol gold mine and mill at the base of Mine Mountain.

The mine was named after Frank Cox and George Bolyan, two of the discoverers. Other people involved with the mine were Frank’s brother Ed Cox, and Ollie Lohberg. Geographic names in this area are confusing; what is currently known as Goulding Harbor was called Pinta Bay in the 1920s, what is now called Pinta Bay was named Deep Bay at the time. Adding to the confusion, Cox and Bolyan also opened another Cobol mine and started a town named Cobol farther South on Chichagof Island around the same time period.

Arthur F. Buddington photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

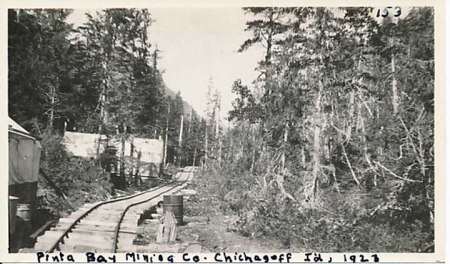

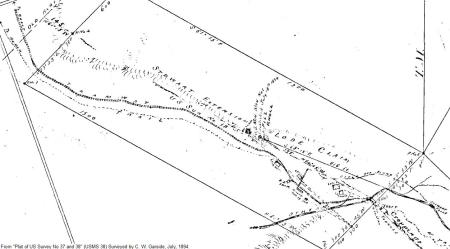

The railroad track was reportedly laid around 1923 by the Pinta Bay Mining Company, who leased the property from Cox and Bolyan. The USGS Mineral Resource Database refers to this line as a “5 mi. long railroad tramway”. A 1923 USGS Bulletin also refers to this line as a railroad, stating:

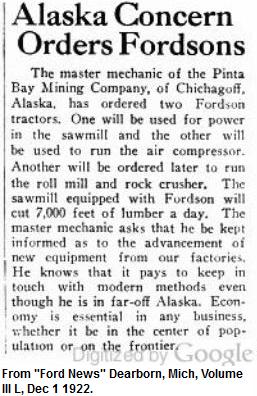

“A light narrow-gauge 30-inch track with 12-pound rails is being built to the mill site, which lies near the tunnel entrance 4 1/2 miles from the beach at the head of Pinta Bay… The railroad is being built to furnish a means of taking in a compressor and the mill parts… a Fordson tractor and trailers for hauling supplies on the railroad. The tractor is specially built and slung on flanged wheels.” (From Buddington, A. F. “Mineral Investigations in Southeastern Alaska” USGS 1923)

A 1949 document mentions that the property reverted to the discoverers around 1933. Cox et al did further development work and produced some gold, then apparently abandoned the property around 1936. The mill and equipment were reportedly removed from the Goulding Harbor site that year. Some prospecting continued at this location, although 1940s reports described the “light rail tramway” as broken down and unusable. The mine was restaked in 1963 and claims remained active until 1976, but no claims are listed there today.

After 1936, the rails and Fordson engine were reportedly removed and used at another nearby mine, possibly the other Cobol. The lower half of the locomotive was left behind and is still visible on the trail which follows the old grade.

“The remains of an old railroad engine are rusting away along this portion of the trail, which generally follows the lower part of an abandoned mining tramway which ran from Goulding Harbor to Mine Mountain during active mining in the 1930s” From 2006 Sitka Coastal Management Plan draft.

Fordson locomotive remains at Goulding Harbor:

Fordson tractors were popular for construction of ad-hoc narrow-gauge locomotives. There was no Ford-sanctioned design, but certain manufacturers had standard conversion models available. There were also home-brew models built by small industries. The design seen in Jack Calvin’s photo resembles a Skagit Steel and Iron type that was used elsewhere, including Nome and the White Pass & Yukon Railroad. Two of the large drive wheels seems to have come off, and based on the axle and connecting rod locations, the smaller wheel with brake pad is not original to the design. Someone may have taken an axle off an ore car and stuck it under the locomotive frame for show.

Some other Fordson locomotives can be seen here. These tractors seemed to be popular with Cobol’s management, as they were used to run other equipment and were used at the second Cobol mine as well. A snippet from the 1922 Ford News notes some of their orders:

________________________________________________________

Lockanok Railroad

(I would like to thank historian Bob King for his help in polishing up this section. His Bristol Bay knowledge, and his proofreading, are greatly appreciated. John Branson of the National Park Service also provided some helpful information).

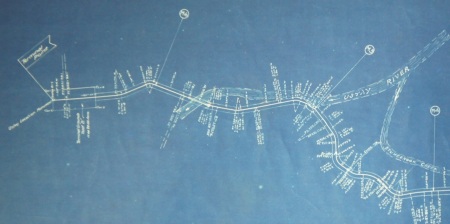

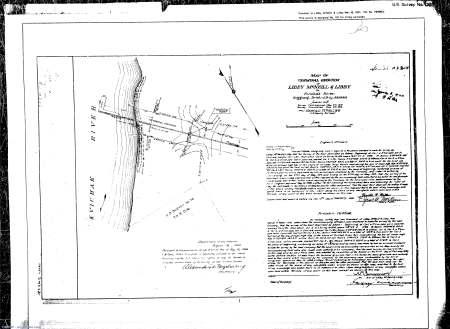

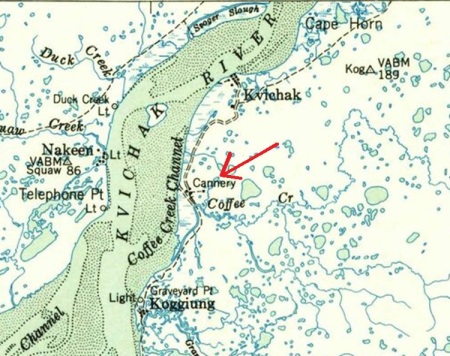

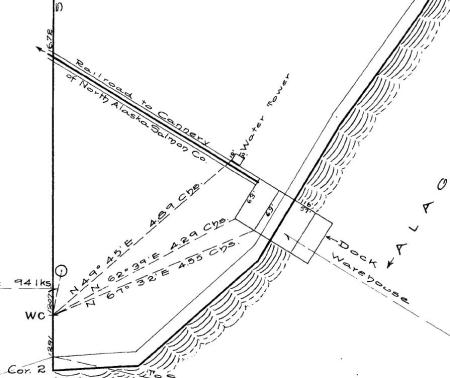

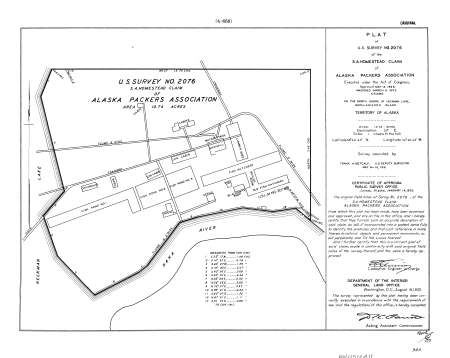

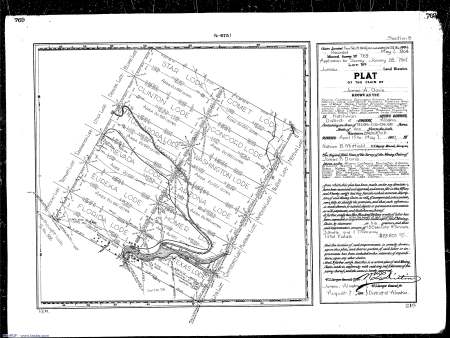

A half-mile rail line linked the Lockanok cannery on Bristol Bay’s Kvichak River to a dock on the nearby Alagnak River. It appears on topographic maps as an abandoned railroad. U.S. Survey 913 from 1912 shows a “Railroad to Cannery” from the Alagnak River, starting at the “homestead” of C.P. Hale. As mentioned elsewhere, cannerymen often used homestead claims to acquire industrial land or tie up land that could have been suitable for competitors.

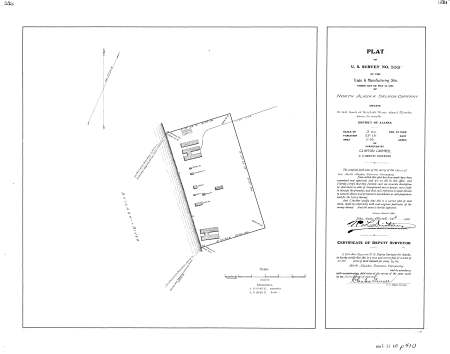

The survey notes for this plat call the line a “narrow gauge railway on 8′ trestle” and describe its value as $200 per chain (a survey chain is 66ft long)

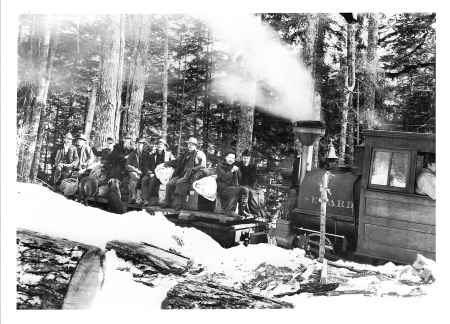

A Wikipedia entry on Crescent Porter Hale notes that shifting mud flats blocked access on the Kvichak to his Lockanok (or Lockenok, a corruption of the Native word Alagnak) cannery in 1912. To maintain access he staked this homestead claim and built a “short rail line” linking the cannery to the adjacent Alagnak River. The line used trains of flatcars pulled by open locomotive “speeders” powered by one or two cylinder Atlas gasoline engines.

Hale was general superintendent of the North Alaska Salmon Company, headed up by fellow San Franciscan Joseph Peter Haller (1856?-1915). The company owned three other canneries in Bristol Bay including the “Hallerville” (sometimes spelled “Hallersville”) cannery two miles upriver of Lockanok. A National Park Service history says the “narrow gauge railroad” connected the Lockanok and Hallerville canneries.

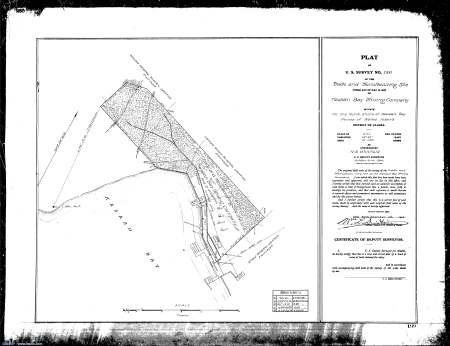

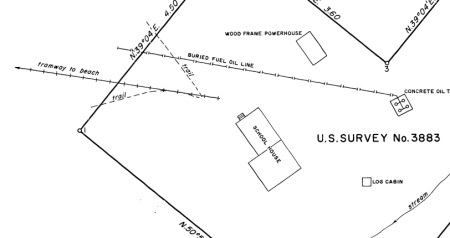

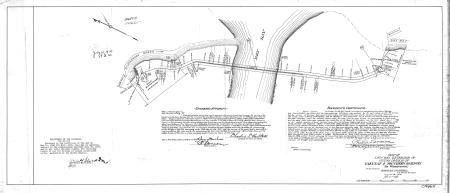

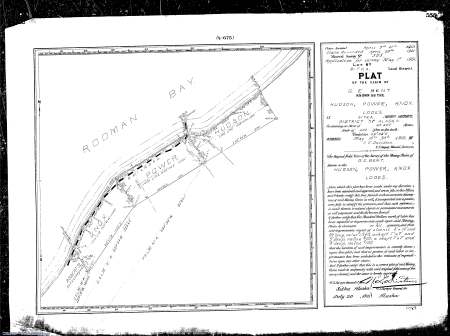

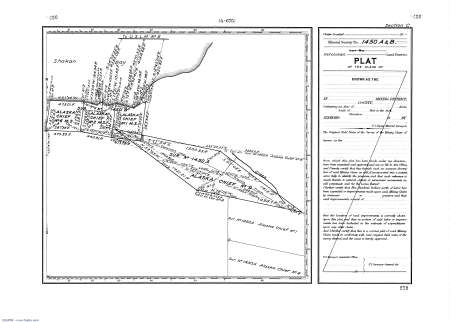

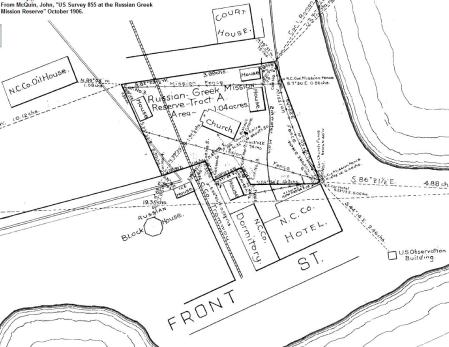

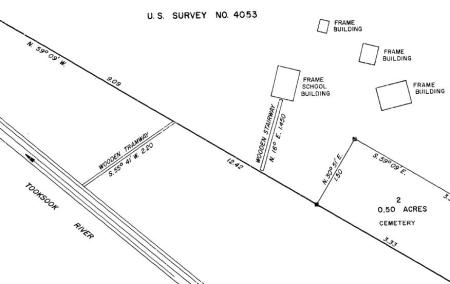

Survey plat showing the two cannery buildings at Lockanok:

Mud flats continued to plague both locations. In 1913 Hale abandoned Hallerville and moved its equipment to a new location on Kvichak Bay just above Naknek’s Pederson Point. After the death of Haller in 1915, Libby, McNeill, and Libby bought all the North Alaska Salmon Co’s canneries. The relocated Hallerville cannery was renamed Libbyville and operated until 1948. The Lockanok cannery operated until 1936 when the continued growth of mudflats forced it to be abandoned. The cannery burned to the ground in 1939 but the rail tracks still remain. Little remains at the original Hallerville site except a few trapper cabins.

________________________________________________________

Killisnoo Tramway

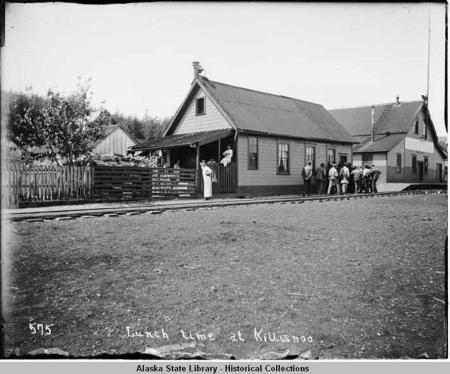

The Killisnoo herring plant on Southern Admiralty Island is shown with a multi-branched tramway on an 1891 survey and on later charts. You can see glimpses of the tracks here and here. What looks like a station platform is shown at right, below (it may simply be a boardwalk). This tram was likely horse-drawn or human-pushed, and seems to have had wooden rails. The layout suggests it was mainly to move freight between steamships and various parts of the plant.

Courtesy of the Alaska State Library, Vincent Soboleff Photograph Collection, P1-261.

More photos of the tracks on the Killisnoo wharf are shown below, including some photos of the rolling stock (small flat cars):

Killisnoo Wharf with loaded tram car.

Killisnoo Wharf in winter.

“Railroad Tracks on Wharf”.

Wharf with tram and steamship docked.

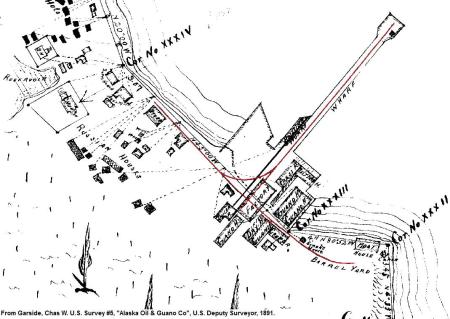

Map of Killisnoo tram tracks in 1891:

The plant originally began as a whaling station before switching to herring oil production. Many whaling stations had small railroad or tram lines, such as these in the South Atlantic.

Map of Killisnoo showing tracks in 1940 (the long wharf seems to have collapsed or been removed):

________________________________________________________

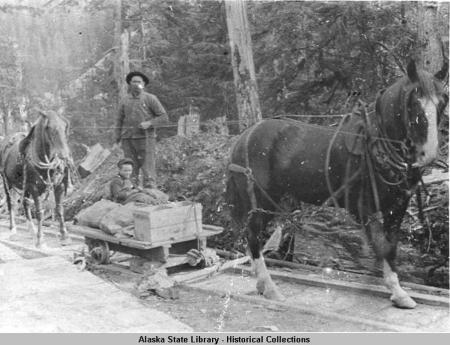

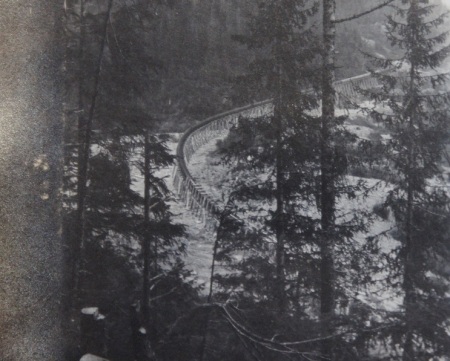

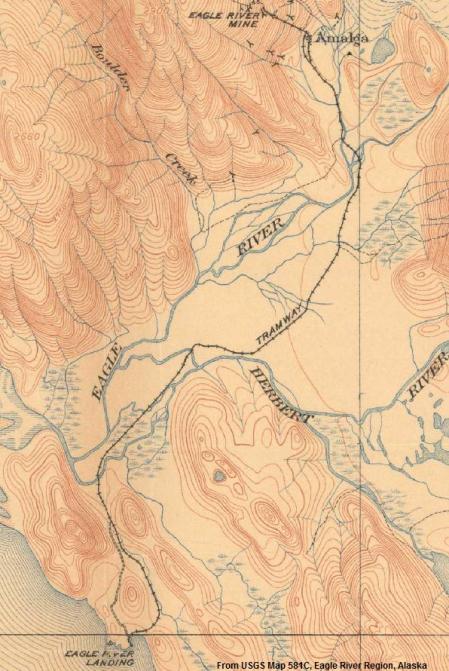

Eagle Harbor / Amalga

A tramway ran from Eagle Harbor to the small town of Amalga just North of Juneau, serving the Eagle River, Bessie, and Amalga gold mines. This is reported to have been “Six miles of horse tram” (some sources say seven miles) and had wooden rails as seen below. Mining began at Amalga around 1902 and the tram was probably constructed by 1903 to bring in stamp mill equipment.

Courtesy of the Alaska State Library, Winter & Pond Photograph Collection, P87-0510.

Town of Amalga with rails between buildings leading away towards the beach:

Courtesy of Alaska State Archives, Winter & Pond Collection, PCA 087.

A ground level view of Amalga with the tram and horses is here.

A photo showing a “Bridge on the Eagle River train line” around 1910.

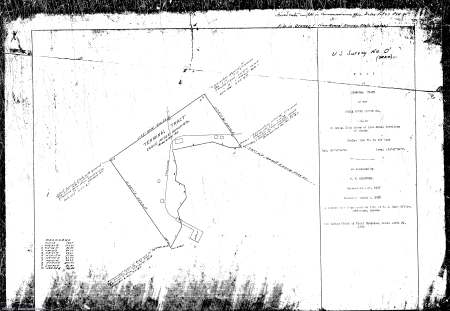

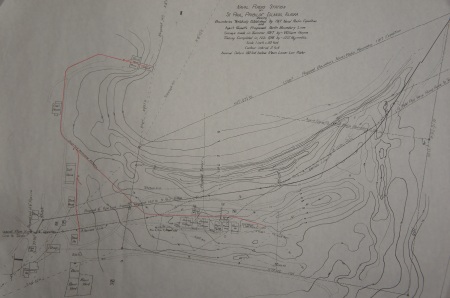

1917 survey showing the terminal grounds of the tramway at Eagle Harbor, with the company’s wharf:

Some additional information on the harbor end of the tram is available here. The tramway and bridges were extensively repaired in 1915 due to flood damage. The mine closed by 1916, although some minor prospecting was done in 1933.

________________________________________________________

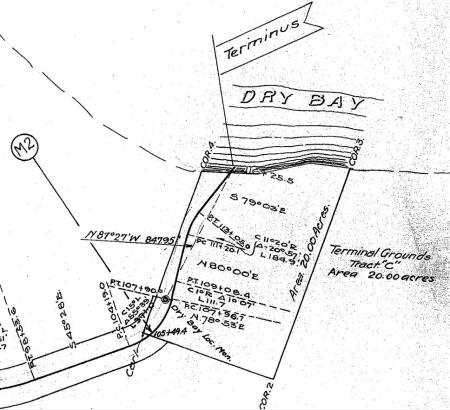

Dry Bay Railroad

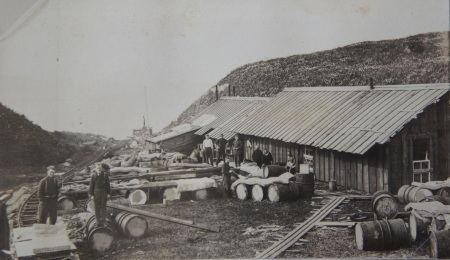

A short railroad was begun in 1909 or 1910 at Dry Bay by the St. Elias Packing Co. This company opened a cannery at the mouth of the Alsek River, and built the rail line to link the cannery to a nearby pier. This operation was closely tied to the Yakutat & Southern Railroad, and was at times technically part of the Y&SRR despite not being connected by rail. Construction continued through 1911, when a US Bureau of Fisheries report lists 21 men employed as “Railway Construction Gang”.

The cannery was built near a prior saltery operation of the Alsek Fisheries Co, which began in 1907 under Capt. Malcolm Campbell and T.E.P. Keegan, and ran until 1910. Campbell was reportedly still active in the area in 1913, running a mild-cure operation from the schooner Standard Fish Co No 2. He also skippered several cannery boats in the intervening years.

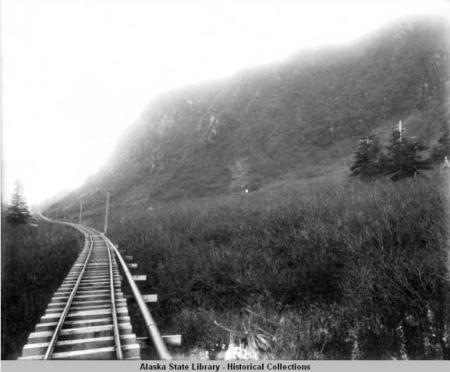

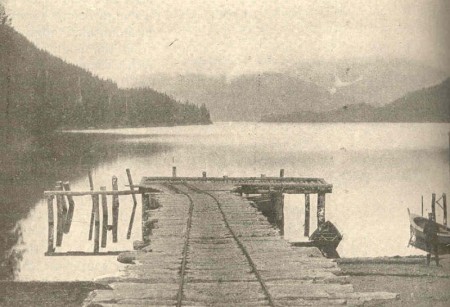

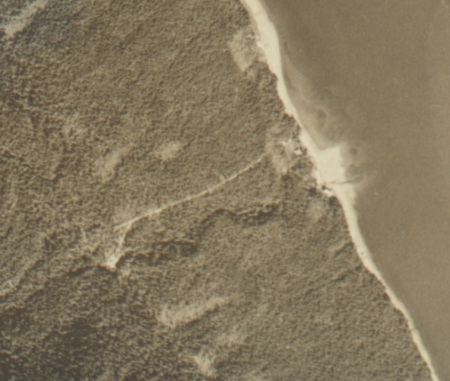

Topo maps show the railroad grade from the cannery to deep water about 1.5 miles away. A 1919 survey shows the line reaching just over 2 miles, with a trestle across a branch of Dry Bay to an island which no longer exists. Shifting tide flats constantly changed the layout of this area, causing ongoing trouble for vessels and structures.

The owner/manager of the cannery in 1911 was listed as R. A. Leonard, formerly of the Columbia Canning Co of Haines. He is also listed as the master of the 103′ wooden ship Oakland which sank at Dry Bay in October of 1912 (all crew were rescued, but the ship and cargo were lost). Captain Malcolm Campbell had also skippered the Oakland for Leonard.

Leonard’s Dry Bay cannery was purchased by Gorman and Company prior to 1912, (they are listed as the home office of the company in 1911, and bought the Y&SRR around the same time). The cannery reportedly closed in 1913. The property was purchased by Libby, McNeil and Libby in 1916 (again, this company also bought the Y&SRR). Fish were apparently still bought to the Dry Bay wharf but were then taken to Yakutat for processing, the Dry Bay cannery being used only for storage. A 1925 memo from the US Dept. of the Interior states that the railroad was not operated after Libby, McNeil & Libby acquired it.

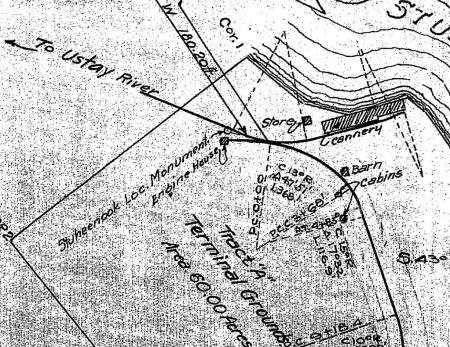

In 1919, the Yakutat & Southern Railway filed a route survey covering the Dry Bay cannery, showing the existing line from wharf to cannery, plus a branch leading towards the Ustay River. This was referred to as “The Dry Bay Extension of the Ustay Division of the Yakutat And Southern Railway”.

It is not clear how far towards the Ustay River this line reached. Surveys show a planned terminal about 5 miles NW of the cannery on the Ustay River. Local information reports a grade leading NW from the cannery site, and aerial photos show what could be a railroad grade reaching the ocean outlet of the Akwe River (also spelled “Akquay” in 1910). Local reports indicate there was some construction in the direction of Yakutat from the cannery. As early as 1901 the Y&SRR had planned to lay track from Yakutat to Dry Bay, serving canneries and fish buying stations at each river along the way. The cost of bridges was found prohibitive and the main line from Yakutat never reached farther than the Situk River. At some point the Ustay River appears to have shifted its course from West to East, leaving the terminal site landlocked.

From Hubbel, Charles S. “Map of the Ustay Division, Yakutat & Southern Railroad” 1919. Courtesy of Alaska State Archives, George Danner Map Collection, MS 262

Rails North shows a Y&SRR locomotive that looks like an 0-4-2 Porter (mislabeled as a Heisler in the first edition of the book) which is probably the one from Dry Bay. The date is listed as 1907, so the Porter was likely at Yakutat before moving to Dry Bay.

A 1966 article in The Trainmaster comments that “there must have been an earlier loco” on the Y&SRR, “Something must have powered the road from its incorp in 1903 until the #2 was bought new in 1907” (Y&SRR #2 was a Lima 2-6-2 steam locomotive, a Heisler “#1” was acquired around 1904 but was reportedly in poor condition and did not meet the line’s needs, later being converted to diesel). Likely the first “#1” mystery locomotive used at Yakutat from 1903-1907 was the Porter 0-4-2. The gauge of the Dry Bay line is uncertain, track from Yakutat to Situk was most recently standard-gauge, but could have begun as narrow gauge. Photos from around 1914 appear to show dual-gauge track (both narrow and standard) on the Yakutat cannery dock. A 1992 study described the Dry Bay cannery line as narrow gauge.

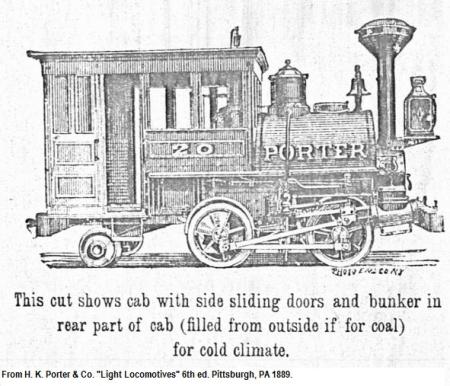

The Porter could have been surplus from Y&SRR president Fred Stimson’s family business, a logging company in Washington state which owned several locomotives. Stimson’s father T.D. Stimson also owned a lumber company in Michigan and used several 15-ton Porter locomotives. One, named “Little T.D.” was C/N 665 built in 1885, and another named “James Roe” was CN 524 built in 1882. Both match the design seen at Dry Bay (0-4-2 with rear wood bunker and sliding doors), but both were narrow gauge. The Stimson railroad in Washington State was standard gauge.

The Y&SRR’s application for right of way at Dry Bay seems to have met with some opposition from the government. In 1925, the Department of the Interior threatened to rescind public land grants because “The railroad is almost wholly a plant facility of the canneries”, and “does not engage in transportation for the public”. The memo accused the railroad of exploiting the law for the benefit of a private corporation, and gave them notice that permission to use National Forest land would be withdrawn. After several appeals and extensions, the issue seems to have been settled, as the Dry Bay route was approved in 1932 with the company proposing to act as a common carrier.

This book mentions that the Dry Bay railroad was abandoned after an earthquake in 1937 (the sandbars probably shifted to block or damage the wharf). The locomotive was left in-place. This photo shows the abandoned locomotive at Dry Bay. This photo shows some of the tracks.

Pat Roppel provided the following information about this railroad:

-In 1912 the Y&SRR proposed a 50-mile right of way to Dry Bay

-In 1913 timber was cut at Dry Bay for a tram road, but the company went bankrupt the next year.

-In 1916 the track, rails, cars, and a locomotive at Dry Bay were sold (back) to the Y&SRR.

-In 1946 the Y&SRR held a Forest Service special use permit for a 50-mile right of way to Dry Bay.

________________________________________________________

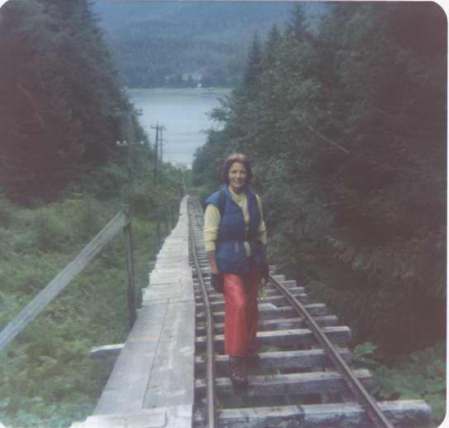

Nugget Creek Tramway

In 1911 the Treadwell mine began constructing a power plant near Mendenhall Glacier in Juneau. This involved damming Nugget Creek, drilling a 650ft tunnel to tap the creek, and running a pipeline from the tunnel to a hydroelectric plant near the present-day glacier visitor’s center.

Photo courtesy of Bill Binns, used with permission.

Rails ran from the road and construction staging area, past the power house, and up to the tunnel. Cars were pulled up the steep grade to the tunnel by an electric winch (I’m not sure what drove them on the level sections of the line).

Courtesy of the Alaska State Library, Alaska Road Commission Photograph Collection, P61-085-155.

Until a few years ago, you could still find some of the machinery and generators on their foundations in the woods. Many of the remains have been demolished by the city in an effort to limit liability.

Juneau Empire writeup of the Nugget Creek power plant.

Another Empire write-up.

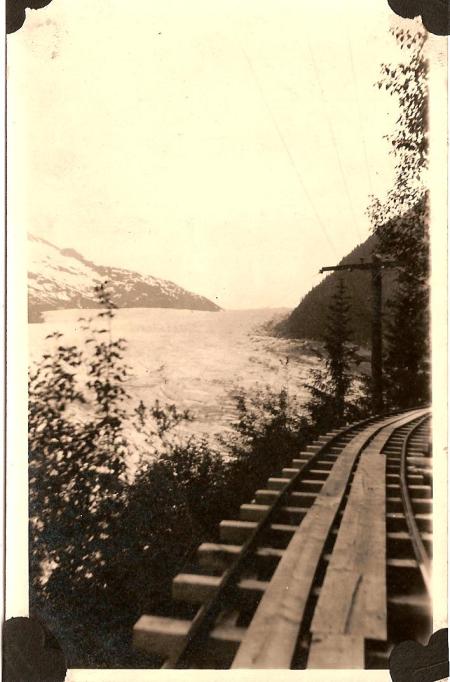

A photo showing the drop to the steep section of tramway, with Mendenhall Glacier in the background.

Another photo shows one of the cars, a wagon with large flanged wheels:

And this photo shows the tram at the tunnel entrance, with what is probably Mendenhall Glacier in the background. Several women are standing around the track (apparently a plank tram here), with an ore car behind them:

Juneau historian Brian Weed has a modern view out of the same tunnel here.

Photo of tramway passing power plant.

Another photo of the tramway passing the plant.

Some contributed photos of Mendenhall tramway remnants:

A rail car in the woods, it appears to be a typical ore cart:

Hoist for the inclined section of the tram:

________________________________________________________

Fortmann Hatchery Tram

The Alaska Packers Association’s Fortmann Hatchery near Loring, AK had a “tramway several miles long” . The last photo on this page shows the tram, which appears to be a wooden plank road. The line is labeled as a “Tram Road” on one survey and as a tramway on another. Cars were likely pushed by hand or possibly pulled by horses. This may not have been a single stretch of track, or even a single type or gauge of track, but rather multiple tramways portaging between lakes. A publication from 1904 describes the following route to reach the hatchery:

“…Up Naha River one-fourth mile to Smokehouse Tramway, on Tramway 1 1/2 miles to Jordan Lake, across Jordan Lake one mile to Windlass Tramway, on Tramway three-fourths mile to Heckman Lake, across Heckman Lake two miles to hatchery at head of lake, on Naha River”

This photo shows what appears to be a rail cart in the background (on the left). I am not sure if this is at the cannery or the hatchery. In addition to the two tramways mentioned in 1904, there are several tramways shown on survey plats of the hatchery complex:

A report from 1904 mentions a tramway 5,524′ long built to move materials for a pipeline from a spring to the cannery. The project apparently included 2,000ft of trestle and a tunnel between Patching and Heckman lakes.

Below are a few more photos of the tramway. So far I have not found any pictures of remaining rolling stock, modern-day portaging seems to require people to drag their boats along the planks of the route.

“Naha railway” upper end

Canoe on tramway

Salt water end of tram, leading into water

Hauling a larger skiff onto the tramway

Tramway alongside river

________________________________________________________

Pribilof Island Trams

Saint Paul Island seems to have had a tramway as early as 1898, when the Alaska Commercial Company introduced “a moveable railway track placed on the beach, extending into deep water, so that boats come to and discharge their freight into cars to be hauled on shore”. This may have been akin to Decauville track, something similar was also used at the A. C. Co’s coal depot at Unalaska.

Boat landing at St. Paul, from Record Group 22 of the US Fish & Wildlife Service. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/23854005

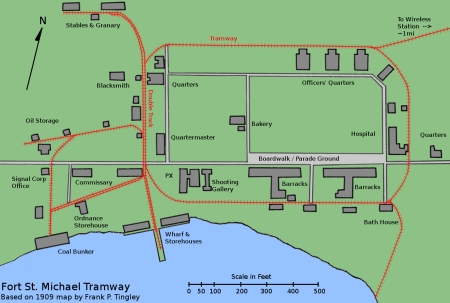

St. Paul and St. George islands had more permanent tramways installed by the US Navy around 1911-1912. These supported construction and supply of radio stations, including hauling fuel drums for generators. The lines ran from the wharf to the radio station on St. George, and to various points in the village of St. Paul. The layout at St. Paul suggests the Navy tramway also supported seal harvests, as it ran to the salt houses and government warehouses.

Track through warehouse from wharf at top right, with small flatcar at bottom center. Image courtesy of NOAA

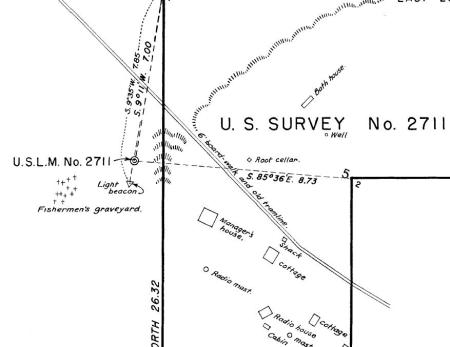

This map from 1915 shows tracks leading to various buildings in the village of Saint Paul. A 1917 map labels this as “Railway Track (2ft Gauge)”. A similar map for St. George Island shows the tramway there, of a simpler design (a straight shot from warehouse to radio station with a branch to the wharf). It appears to be labeled “RR Track (2ft Gauge)”

Patrick Durand and Dick Morris with the Engine 557 Restoration Company were kind enough to send me a 1917 map of the Naval Radio Station and tramway. I’ve traced the track in red to highlight it in the copy below. This map omits the spur to the cold storage near the wharf, which could have been added later in 1917.

More photos of St Paul village showing the Navy tramway are available below:

Tram tracks in background

Tracks past boats and bags near wharf

Tracks leading towards radio station

Tracks in 1940 being used to store barrels (middle of photo, wooden ramps seem to be unrelated).

Photo showing “Machine Shop Railroad” on St. Paul Island:

Other tramways reportedly supported seal harvests (both islands were government-controlled sealing operations for many decades). The tracks may have run from the rookeries to the main port or village area. One or both of these may have actually been a plank road, as seen here. Here is another photo of the plank road on St. George. One report called for construction of a 12-mile tramway powered by a gasoline engine on St. Paul Island. A Bureau of Fisheries report from 1922 describes wooden tracks for trucks and tractors “over the worst stretches of sand”, and also mentions that heavy seas destroyed the St. George wharf tramway in 1921.

________________________________________________________

Chickaloon Tram

A photo in the Alaska Digital archives shows an incline tram “connecting old and new Chickaloon” in 1921. Another view is here. This was likely associated with the coal mines in the area. The Alaska Railroad had a spur to the region that was abandoned in the 1930s.

Patrick Durand reports that Old Chickaloon was on the river bottom and had the railroad terminus. New Chickaloon was built at the top of the hill by the Navy, the coal mines were developed as a fuel source for the Navy’s North Pacific Fleet. The incline tram moved materials from track side to the new town site. The buildings and track were mostly removed by 1928.

________________________________________________________

Sitka Pulp Mill Rail Yard

In recent times, several Alaskan port cities have had stub rail yards with only barge access in or out (Such as CN’s Aquatrain). This theoretically allowed more efficient bulk transport, as entire train cars of product could be shipped to and from the state without repackaging. Rail barges are also used between the Alaska Railroad and Outside lines (One of the stranger imports is Lower-48 graffiti, the spraypaint “art” on rail cars from Down South is usually much high quality than local Alaskan taggers can manage).

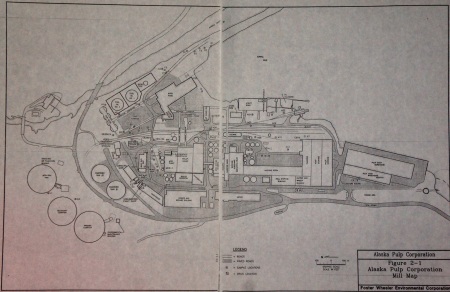

Sitka had a rail yard at the Alaska Pulp Corporation’s mill in Silver Bay. Cars of chemicals were brought in, and cars of pulp products taken out. At least one diesel switcher stayed on-site. John Taubeneck reports that the mill had a 400hp, 65ton GE center cab locomotive built in 1943 for the US Navy, which was transferred to Cleveland Ohio after the mill closed. The Sitka mill shut down in 1993 and the site was donated to the City in 1999. Most of the rail yard has probably been ripped out during ongoing demolition and redevelopment of the site.

Incidentally, the hydroelectric dam and power tunnel built for this pulp mill also involved a small construction or mining tramway, seen in a 1958 newspaper photo. This seems to have been mostly underground for mucking out the headrace tunnel, as with other Alaska hydro projects. The tracks and cars probably belonged to a contractor and were removed after completion.

________________________________________________________

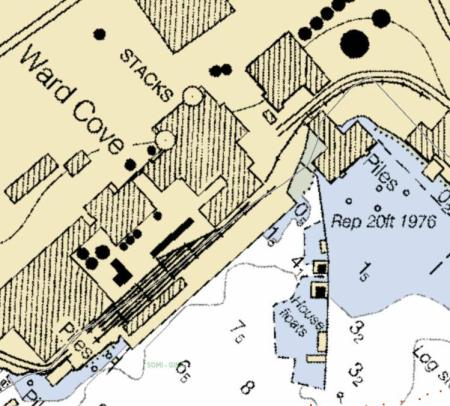

Ward’s Cove Rail Yard

Like the pulp mill at Sitka, the Ketchikan Pulp Co had a yard and rail barge dock at the Ward’s Cove mill. At least two switch engines operated there, including a 50-ton Whitcomb B-B diesel center-cab, #61279. Some photos and information are available here.

________________________________________________________

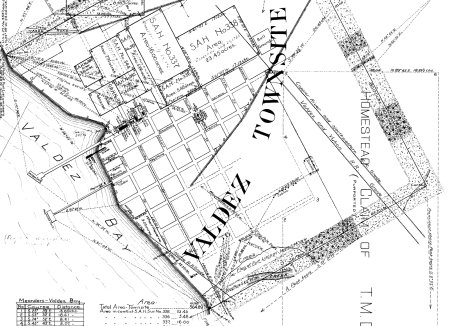

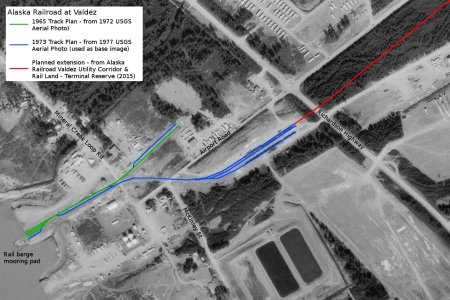

Valdez Railroads

While mentioned in several other publications, few books fully cover the four(!) different railroads which have laid track in the town of Valdez. These include the Copper River & Northwestern, the Valdez Yukon RR, the Alaska Home RR, and even the Alaska Railroad.

Several abandoned railroad projects at Valdez have left their mark in cuttings and tunnels around town. The closest to being realized was the Alaska Home Railway, which purported to be constructing an electric line to Fairbanks. The company brought in at least one steam locomotive and laid a mile of track, but turned out to be largely fraudulent. Another company was the Valdez-Yukon Railway, who graded 10 miles, laid some track, and brought in some rolling stock. They supposedly owned a large locomotive but never shipped it to Alaska. The Copper River and Northwestern RR also started grading work at Valdez prior to 1909, but abandoned the area in favor of Cordova. This company dug a tunnel and laid some narrow-gauge track, but may not have advanced to putting down standard-gauge rails. After rival railroad crews had a shootout in nearby Keystone Canyon, all work was abandoned. The town of Valdez was left nearly bankrupt after investing heavily in various railroad scams.

Alaska Home Railway operating their steam locomotive.

Valdez Yukon work car.

Valdez-Yukon “Roundhouse”

Valdez-Yukon wharf and flatcars.

Copper River Nothwestern Tunnel and rails.

Valdez had another rail-barge port and short industrial line. This was technically part of the Alaska Railroad. It was originally installed around 1965 to aid in rebuilding Valdez after the 1964 earthquake (source). The yard was expanded in 1973 for pipeline construction. This port does not seem to have had an adjustable rail bridge, barges were beached on a pad and allowed to go dry at low tide, when the decks would line up with the railroad grade on shore.

During the Trans-Alaska pipeline boom, a rather odd logistical situation developed. Pipe sections were apparently brought to Whittier on flatcars by Hydro-Train, back-loaded onto smaller barges, taken to Valdez to be connected at a welding plant, then shipped back to Whittier for transport North. The road out of Valdez could not handle the longer pipes, and Whittier had so little flat land that there was no space for a welding plant. This complex dance of pipes likely could have been avoided by simply doing the welding in Anchorage or elsewhere on the Alaska Railroad mainline. It appears to be one of those very Alaskan schemes designed to squeeze extra money out of unsuspecting investors “Down South”.

More photos are here. Some additional details are here.

The tracks seem to have been removed after the pipeline boom, although the Alaska Railroad still owns a terminal reserve at Valdez, with right-of way extending past the 1970s rail yard towards the airport.

US Survey Plat 439, based on 1909 surveys, showing multiple railroad grades at Valdez.

________________________________________________________

Saxman Rail Barge Terminal

Saxman, a suburb of Ketchikan, had a small rail barge terminal and curving track with at least one siding at the Saxman Seaport. It was built around 1967 (another site says 1964) to be a container port for the Ketchikan area. Motive power was apparently something like a trackmobile. In 1977 the site was known as the Ketchikan and Northern Terminal, and handled 25% of Southeast Alaska’s total freight. About 4,000 tons of propane were brought in each year in 60 rail cars (source). The site looks somewhat derelict in recent aerial and ground photos, and the rail ramp is listed as a “dynamite loading dock“. A government study from 2012 proposes to pave over the tracks and use the site for container unloading.

More recent aerial photos (2022) show the rails mostly buried under dirt, and the barge ramp replaced with a small boat dock.

________________________________________________________

Trans-Alaska Railroad / Alaska Short Line Railroad

Howard Clifford reported that work began in the early 1900s on a railroad between Williamsport at Iliamna Bay and Railroad City on the Yukon River near Holy Cross. Supposedly this progressed to the point of laying some track in the area of Old Iliamna and blasting at least part of a tunnel (probably through the Chigmit Mountains). A Fairbanks Daily News-Miner article also mentions track laid at both ends of the line, and Bob DeArmond mentions that steel rails were shipped to Illiamna Bay around 1904. Another shipment of rails was lost when the steamer Farallon was shipwrecked in Illiamna Bay in 1910.

Evidence of an overgrown railroad grade can be seen South of the present day Williamsport – Pile Bay Road.

This line seems to have had several names and backers. The Trans-Alaska Co laid out a trail along the route in 1902, but then folded. Several sources such as this and this indicate that they planned or began a horse tramway from Iliamna to St. Michael, with roadhouses every 25-30 miles. This seems like an excessive distance for a horse tram.

The Alaska Short Line Co took over the project soon afterward, running surveys from 1903-1908. A 1906 journal describes the route as “Iliamna Bay or Kamishak Bay to Anvik”, with Joseph Taylor Cornforth as president and W.E. Smith as chief engineer of the Alaska Development & Construction Company. Cornforth was apparently involved with all of these companies, as well as a steamship line proposed to serve Iliamna Bay in 1902.

Railroad City originated as a horse camp for surveyors around 1901, with the Alaska Shortline Railway and Navigation Co planning to develop agriculture in the Yukon River Valley. The company later decided that the railroad should be located along a different route and abandoned the town (source). Clifford reports that some of the equipment still remains in place at both of these ghost towns. Railroad City was renamed Red Wing for a time and operated as a transshipment point by the Northern Commercial Company for freight to Iditarod and Flat. The Standard Oil Co also had tanks and a fueling station at Railroad City in the 1930s. A survey from the 1980s mentions “numerous dilapidated cabins” at the site.

In 1910 the Alaska Short Line Railway and Navigation Co requested more time from Congress to prove up their right-of-way claims, as they had not been able to start construction. A 1910 journal noted that the right of way was acquired that year by a syndicate headed by A. J. (Arnold) Schuer. The News-Miner also mentions a “Free Love Society” as being involved. This book describes one of the planned routes, and notes that a branch to Bristol Bay was considered to serve canneries in the area.

________________________________________________________

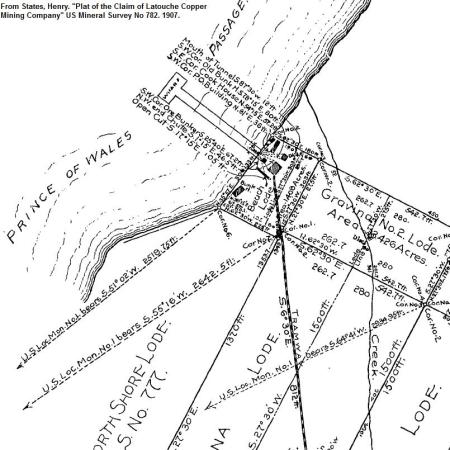

Rush & Brown Mine Railroad

Located on Prince of Wales Island, this copper-nickel mine had a railway leading about 3 miles to a deep-water wharf. A freighter at the wharf can be seen here. The mine used a Porter 0-4-2 locomotive with rear tank to haul ore trains.

The Rush and Brown mine was discovered around 1904 (some sources say 1900) by U. S. Rush and George E. Brown, and operated from about 1906 to 1923 under the Alaska Copper Company. A note in the March 2, 1906 issue of the San Francisco Call states that:

“The forest service has granted to the Alaska Copper Company the right of way for the construction of a narrow-gauge locomotive tramway within the Alexander Archipelago forest reserve, Alaska”. (San Francisco Call, Vol 99, No 92, pg. 2, 2 March 1906).

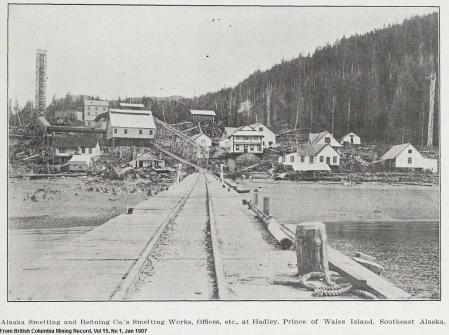

Despite being a consistent producer and operating for many years, the mine did not have a very large output. It used lower-cost methods of excavating and was generally known for being frugal. Workings included underground tunnels and shafts, as well as a large open pit “glory hole”. The Alaska Copper Co built their own smelter at Coppermount on the other side of Prince of Wales Island, but this was unable to withstand price fluctuations in 1907 and closed, as did the other major smelter at Hadley. The Rush & Brown mine closed in 1923 due to low copper prices and difficulty securing a smelting contract.

The Solar Development Co optioned the property in 1929, pumped out the workings, and began a new adit, but no major work appears to have been done after that. A 1937 report states that “The railway, which is 42 inch gauge, 16lb. rails will require a considerable expenditure of money although light loads approximating 2000lbs were taken over it during the last summer and fall.” By 1948, the railway was reported “completely deteriorated, except that 2 miles of 16-lb rails remain”.

In Fortunes from the Earth, historian Pat Roppel describes the locomotive as an 8-ton H.K. Porter, hauling steel cars of 50-ton capacity. The locomotive was recovered in the 1970s and is partway through restoration.

According to steamlocomotive.com, the Rush & Brown locomotive came from the Albany (Oregon) Street Railway, and was a former steam dummy (construction number 1392). This street railway operated from 1889-1918. It originally used horses, then acquired a newly-built steam dummy engine (named “Goltra Park”) in 1892. The steam dummy broke down in 1900 and was abandoned (one source says the cab burned off). Another H.K. Porter locomotive with a normal cab was purchased in 1903 and used until 1908 when electric locomotives took over. The gauge is listed as 3’6″, or 42″. Albany’s steam dummy is seen here, and the normal-cab Porter is shown here. Both appear to be 0-4-2 locomotives, but the regular-cab Porter looks more like the locomotive which came from Rush and Brown. A post on this forum states that the steam dummy was salvaged and converted to a normal cab after Albany abandoned it.

The Rush and Brown later combined some operations with the nearby Salt Chuck Mine. Patricia Roppel reports that ore was brought from Rush and Brown to Salt Chuck using a Mancha storage battery locomotive, which can still be found near the Salt Chuck mill site.

________________________________________________________

New Boston Mine.

The New Boston Mine on Douglas Island had a 2,800-foot long tramway around 1887, from the mine to a wharf on Gastineau Channel. The mine was not productive, and in 1889 the rails from the tram were moved to the Douglas sawmill. (Per Bureau of Mines Mineral Investigations in the Juneau Mining District, Alaska, 1984-1988). The sawmill was connected by rail to the Treadwell mine, the equipment could have been re-used on that line or used for hauling logs out of the water.

________________________________________________________

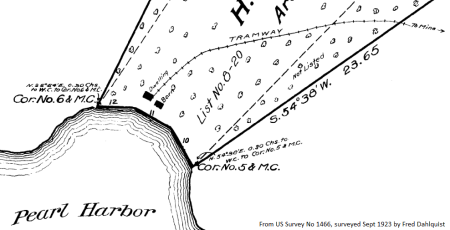

Peterson Mine & Pearl Harbor Tram

The Peterson Mine (started around 1897) had a 4-mile horse-drawn tramway to Pearl Harbor, north of Juneau. The route is now a public hiking trail and remnants of the wooden tram (with metal straps to guide cars) are still visible. The tram was reportedly built around 1903 by Tom Drew. One government report said that mules pulled 1.5-ton cars, and that steep grades prohibited heavier loads.

Photo of tramway rails

Photo showing metal strap rails on wood tramway.

Slideshow with more photos of the trail and tram remnants.

Rails at Pearl Harbor (this could be a marine railway).

A rail cart found nearby, possibly from this tramway.

The mine was founded by John Peterson, and operated by his entire family. When John died in 1916, his wife Marie and their two daughters continued to operate the mine, doing everything from the drilling and blasting to blacksmithing and tramming. A mine run by three women was somewhat unique at the time, but Alaskan women tend to do well in unconventional activities. More information is in part one and part two of a 2011 Juneau Empire article.

________________________________________________________

Penn Alaska Tram

A short tramway with two stations is shown at the Penn Alaska mine on Taku Inlet. This mine dates from around 1906. Other documents show slightly different alignments for the track, with at least one showing the “road” as another branch of the tram. A report from 1911 describes this as “wood rail tramway”.

________________________________________________________

Crystal & Friday Tramway

A tramway (or “tramline”) with several branches ran between various mines in the Snettisham area (the historic town, not the present hydropower station). One branch connected the Crystal Mine to the Friday Mine’s stamp mill. The tram routes are marked as trails on modern topo maps.

The tramways are labeled as “roads” on an 1899 survey, but are depicted with the crosshatches normally used for rail lines. They may have been elevated tramroads with wooden rails.

Gold deposits at both mines were largely exhausted by 1905, with the equipment reportedly removed soon afterwards. Some work continued until the 1920s. Development in this area is currently under review, with a proposal for an iron/titanium mine. The iron ore content of this hillside is so high that navigational charts note a severe magnetic disturbance to compass bearings for passing ships.

________________________________________________________

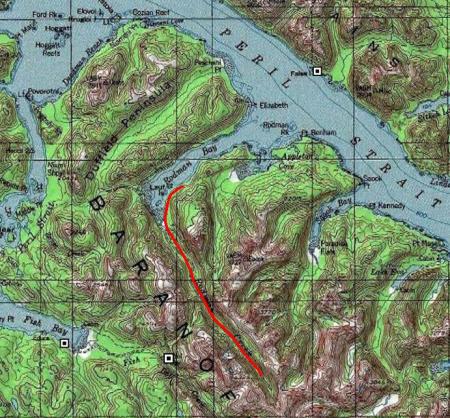

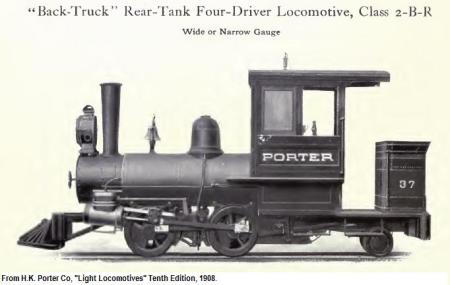

Rodman Bay Railroad

Rodman Bay is located on the North side of Baranof Island, in Peril Strait. From about 1901 to 1904, a railroad ran from the shore to a gold mine on nearby Rodman Creek. The line was approximately 8-10 miles in length. The mine failed after only a few years, by some accounts the deposit was poorer than expected, and by other accounts the entire thing was an investment scam.

The railroad was 30″ gauge and used an H.K. Porter 0-4-4T (or “Forney”) locomotive named “Rodman”. The engine was construction number 2245, built in the fall of 1901 as Engine #1 for the company. This was a slightly larger and more complex engine than typically seen on small Alaska mining railways. It may have been picked up cheaply after an earlier order fell through, as the Porter specification sheet indicates it was originally for the Ray Copper Mines Co of Riverside, AZ. On the sheets, the original order details are crossed out and replaced with the Rodman Bay info. The original Arizona design included a wood-burning stack, but the fuel was changed to coal for use in Alaska. The engine was to be marked:

RODMAN

THE RODMAN BAY CO.

LIMITED

1

Rolling stock is described as five large and three small flat cars, one hand car, one velocipede (a kind of railroad bicycle), and two ore carts.

A Porter 0-4-4T of similar size can be seen here. Pioneer Park in Fairbanks has a replica of an 0-4-4T Porter. A nearly identical design based on Porter’s 1908 catalog is seen below:

Below are a few more historic images of the railroad:

Lumber for mill on flat cars, ca 1900

Trestle and Workers at Rodman Bay, ca 1900.

Railroad Bridge at Rodman Bay, ca 1900.

Tracks along the beach, ca 1900

Boarding house, engine house, and railway tracks.

Sawmill and buildings, railroad visible on right. 1902.

Approximate route of the Rodman Bay Railroad:

Mining claims were located in the area around 1898 by a group of prospectors, including brothers George and James Bent. They were initially financed (or “grubstaked”) by the Alaska-Baranof Exploration Company, incorporated “to build and operate railroads”. Backers included Juneau banker W. T. Summers and Pacific Coast Steamship Co captain James Carroll. Other investors were brought in around 1899, and the company became known as the “Rodman Syndicate”. In 1900, after initial mill tests of local ore proved promising, the syndicate re-organized as the Rodman Bay Company.

Company directors included George B. Hudson, Edmund Rawson, and H. G. Slade. A major investor was Colonel Edward Harrison Power. Colonel Power reportedly won a large amount of money from various casinos, and invested it into the “Alaskan Rodman Bay Railroad”. He was also involved with several street car companies in the US.

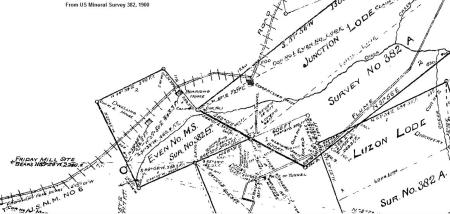

A 1901 survey shows the railroad leading from the wharf towards the mine, across mining claims named after company officials:

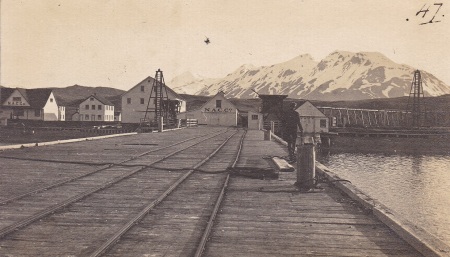

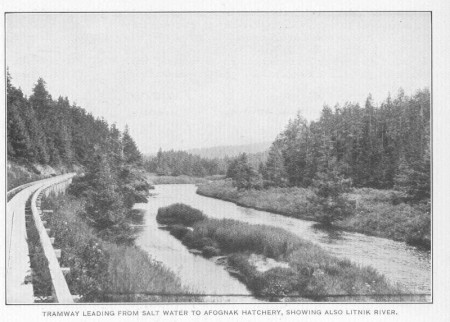

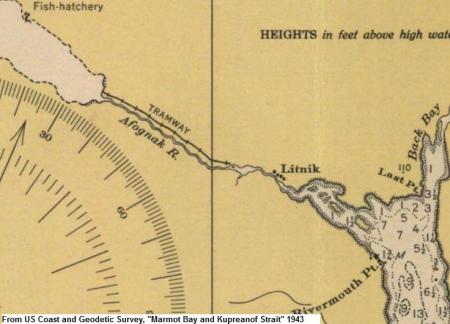

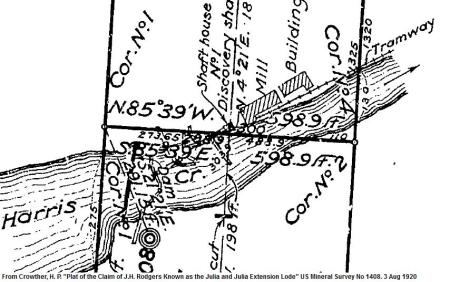

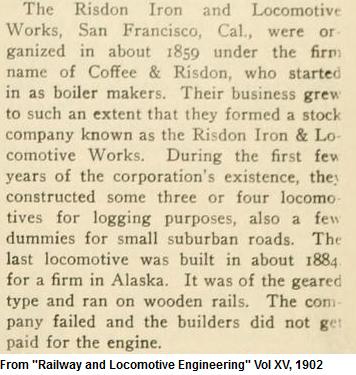

The company began large-scale development of the property in 1901, under the local management of George Bent. A very large tunnel was begun, dimensions are given as 10ft high by 12 feet wide, and about 760ft long. An additional tunnel and shaft were started near the wharf. The stamp mill was planned to have 120 stamps, but only 60 could be delivered by 1902. This publication describes multiple worker’s houses, a bunkhouse for 52 men, an office, a large sawmill, a general store, a stable for 6 horses, a blacksmith shop, storage buildings, compressor, and a roundhouse and water tank for the railroad. The company kept cattle, sheep, and chickens at nearby Appleton Cove to help feed the workers. A post office opened in 1901 and received two mail deliveries per month. The company owned the steamer Tonquin for a few years. Newspaper articles claimed the mine would outdo Treadwell in profits, but this claim was made of almost any new mine in an effort to attract investors.